Revolution #57, August 20, 2006

The Power of Bill T. Jones’ Blind Date: Refusing to Look Away

Bill T. Jones’ Blind Date opens with an inaudible bang. People were still finding their seats at the Lincoln Center theater when words began scrolling down the translucent screens hanging on stage.

“The greatest human crimes have been perpetrated in the name of religion and the name of God.

The clean white letters kept coming. I scrambled for a pen.

“…The knowledge of the natural world and the human world has nothing to do whatsoever with religion and should be approached completely free from religious ideas or convictions.”

|

Blind Date. Dancers (l-r) - Stuart Singer, Wen-Chung Lin, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Donald Shorter, Erick Montes, Premiere performance at Montclair State University, New Jersey, September 2005 |

|

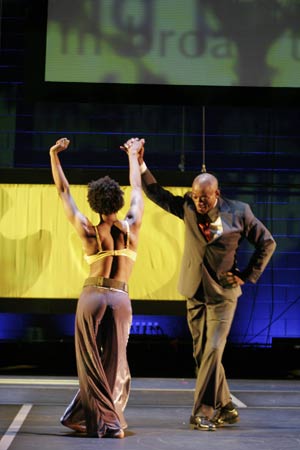

Blind Date. Dancers (l-r) - Shayla-Vie Jenkins, Bill T. Jones, Premiere performance at Montclair State University, New Jersey, September 2005 |

|

Blind Date. Dancer - Leah Co, Preview performance at Aaron Davis Hall in New York City, June 2005 |

Photos all by Paul B. Goode |

This was bracing. On one of New York City’s pre-eminent stages, a dance performance opens up with plain-spoken secular truths. In the Christian-fundamentalist-soaked climate of 2006 America, they came off like fighting words. In fact, these statements are the views of the Enlightenment philosophers of the 18th century, people like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, and Denis Diderot. Ideas that are 250 years old.

Such are the matters on the mind of one of the foremost modern dancers and choreographers in the U.S. today.

Blind Date, a work of beauty and complexity, ranges widely through an American landscape pockmarked by war, military martinets, and religious haranguers. The texts (there were several, not all in English) reappear repeatedly, sometimes projected, sometimes spoken or sung. They’re mixed in with a torrent of high-speed movement, video, and weird spectacle that challenge the audience to think and rethink about patriotism, war, religion, and the dire circumstances of NOW. How can still-thinking people confront all this?

Bill T. Jones, who has been breaking icons and raising the bar in the New York City dance scene for 30 years, has a riveting power and grace on the stage. He leads a troupe of ten younger dancers from the U.S., Mexico, Turkey and Taiwan. They are dazzlingly athletic and of no single pre-set shape or sensibility. (His troupes have been known for being unconventional—having dancers of all different shapes and sizes.)

The stories in Blind Date are told in fragments. Funny and horrifying—these are lives in a blender. A 16-year-old Black youth takes a job luring customers into a Harlem hamburger joint called Quack a Dack. His father says it will give him a sense of purpose. He has to wear a giant round yellow duck head. Military recruiters show up to vie for him. Who says Black kids in Harlem don’t have career choices? A relentless duck theme illustrates the grand variety of ways to get fucked. A row of carnival sitting-duck silhouettes light up overhead… a video screen flashes blood-red ketchup poured over the Quack a Dack burger-meat… the duck head appears on the floor minus its owner… huge dead-duck cut-outs in bloody shrouds are wheeled in for the evening’s climax.

We are also reminded about what is happening to people around the world as someone intones the numbers:

Rwanda—1 million slaughtered in 90 days

9000 dead Hondurans in hurricane

10,000 killed in East Timor civil war

Somebody praise the Lord…

In New York City, September 11, 2900

In Bam, Iran earthquake, 40,000

Somebody praise the Lord…

Then Jones, in a business suit, moves to the front of the stage. He has been asking for cigarettes all night and confides to the audience: “I know what you’re thinking, but I swear I’m going to cut down.” Words of a rapacious vampire or just a chain smoker? You decide.

At one point, company member Shaneeka Harrell belts out a soulful version of Otis Redding’s “Security.”

I want security, yeah

Without it I had a great loss, oh now

Security, yeah

And I want it at any cost, oh now

Don’t want no money, right muh now

I don’t want no fame

But security I have all of these things, yeah…

The stage erupts in a Saturday night bash (to me circa 1969), dancers ricocheting off one another with joyous abandon. The next thing you know, a horror descends as one after the other a dancer shouts “ME!”—then tips over like a felled beanstalk. Others rush to catch them—an exercise in trust that is tender but harrowing. As the pace quickens, heads just miss the floor. My stomach is in knots.

Lone souls declaring their personhood as they fall almost-faster than the collective can rescue them. Isn’t this how it feels to so many people these days? Individuals trying to rely on each other and a badly-fraying social web. Sometimes it works, often you’re just stuck out on your own in a world that’s going nuts, and closing in: You want Security? I’m reminded of the new “post-911 norms” of red alert instructions from your president, your sergeant, your cop, your preacher, and Fox News.

On his web site, Bill T. Jones talks about what provoked Blind Date, which was first staged in September 2005:

“…I was a bit incensed because I thought that certain notions that had been the foundation of American society were being, if not completely eroded, were in fact being discounted. I thought there was a certain intolerance that was creeping into our rabid and confrontational discourse around personal freedom, around ideas of patriotism. I felt threatened as someone who was shaped by notions of the 18th century Enlightenment philosophers. Progress, tolerance, and deism—these ideas are at the basis of our notions of what it means to be a free person. These ideas have shaped me. I am a product of the civil rights struggle and many social struggles…”

The extreme situation Jones alludes to is real, unprecedented. And I would go further: American society is being rapidly remade in a fascist direction by a regime that is going for unchallenged, and unchallenge-able, world hegemony and is answering to religious fanatics who are determined to reverse not just the verdicts of the ‘60s and Roe v. Wade, not just what happened through the Civil War, but to go all the way back to the founding of the country. They want to replace a secular government with biblically-literal theocratic rule. We’re talking no divorce, and the death penalty for straying wives, rebellious children, and those who “leave a stain on society.”

In his program notes, Jones writes: “Like so many others, I see a confrontation between the venerable values we, the modern world’s first democracy, have inherited from the Enlightenment and the anti-intellectual, consumerist, and fundamentalist trends that threaten to highjack our social/political discourse.”

Like millions, Jones feels the gravity of this moment—when so much seems at stake, when the whole future and direction of society seems to hang in the balance. And he feels compelled to sound the alarm, which is the power of Blind Date—refusing to look away. The dangers of the times are—and should—make every thinking and caring person ponder, debate, rethink and struggle over what kind of society we need to truly emancipate humanity.

Still, the “values of the Enlightenment” do divide into two. On the one hand, things like rational thought, science, and secularism did (and do) represent real progress up against religious obscurantism and theocracy. But the Enlightenment, which went along with the birth of “the world’s first modern democracy,” was a part of the growth and consolidation of capitalism as an exploitative system that continues to chew up and destroy the planet and humanity. And in this light it’s worth pondering the fact that the slave-holding founding fathers of America also could enthusiastically embrace 18th century notions of progress, tolerance, and deism.

Interestingly, there are powerful scenes in Blind Date that open up these very contradictions.

Jones at one point duels with his alter-ego, Andrea Smith, dressed in U.S. military fatigues:

A: The first ideal was about honor, valor and courage.

B: Words, Andrea, nothing more than words.

A: More than words!

B: In other words, patriot—that was the idea, right?

A: I have no idea.

B: It was my idea there was a confession behind this idea.

A: Aren’t you a good person?

B: I didn’t say good person, I said patriot.

“I didn’t say good person, I said patriot.”

Now there’s an excellent concept for people to be mulling over upon leaving a theater in the US of A. “Honor, valor and courage” ARE more than words. Their meaning lies in what kind of society you are fighting for, and in Blind Date, I think Jones is asking people to ponder the “confession behind” American patriotism.

This leads me to another question Jones poses to his audience in the program notes: “How does one take a principled stand on a host of issues and not be infected with our era’s great plague ‘toxic certainty’?”

Okay, here’s my answer. There is indeed a kind of “toxic certainty” running through the absolutist mega-churches and spewed from the White House (like “You’re either with us or against us”) that is extremely dangerous and tied to the political program of an empire out to dominate the world. The Bush regime wants to mold an ignorant and compliant populace who are literally afraid of thinking.

But there is a real world that we can learn and know about. And as the words up on the stage of Blind Date put it: “The knowledge of the natural world and the human world has nothing to do whatsoever with religion and should be approached completely free from religious ideas or convictions.” Human beings and society as a whole can’t know everything about the world—which is infinitely complex and constantly changing. But there are real things we can know—with relative certainty. And if we’re going to change the world—and we must—then we need to understand the world and act on certainty, not a rigid, dogmatic certainty, but one based, at each point, on humanity’s best understanding of the truth.

* * * * *

On the night I saw it, at the end of Blind Date after numerous curtain calls, Jones returned to the stage with what seemed like an impromptu afterthought—an angular little solo, punching the air with fierce jabs, like a man determined to escape the confines of his corporate suit and pre-destiny, to go out fighting. A friend who saw the show earlier told me he’d come back onstage that night too and stood for a long moment in a ‘68-Olympics Black power salute.

Jones’ final note in the program: “A basic truth is at work here: just as in life, each participant and observer must make choices.”

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.