Revolution #109, November 18, 2007

| Current Issue | Previous Issues | Bob Avakian | RCP | Topics | Contact Us |

A Life, a Country, a Crucial Moment:

the Film PERSEPOLIS

October 8, 2007. A World to Win News Service. The following review is translated from the Iranian student publication Bazr (no. 20, www.bazr1384.com). The postscript is by AWTW.

Sometimes we forget that history is not a book or an article, that it is life. That we ourselves are part of history, that we live it and make it. And then it is art that reminds us of life beyond everyday drudgeries.

Sometimes we forget that history is not a book or an article, that it is life. That we ourselves are part of history, that we live it and make it. And then it is art that reminds us of life beyond everyday drudgeries.

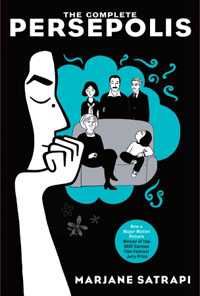

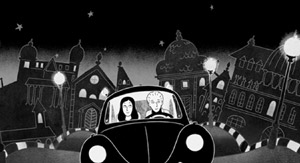

Persepolis, an animated film by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud, is based on the four volumes of Satrapi’s widely read autobiographical graphic novel of the same name. It tells the story of contemporary Iran through the life of a girl with grand ambitions: to be the galaxy’s last prophet and to shave her legs. Contradictory concepts in one existence that throughout the film knit together the turbulent history of Iran and Marjane’s turbulent life. She is nine years old when the waves of revolution rise to engulf the country. Waves that send her parents to the demonstrations, bring politics into her childhood games, free prisoners from the dungeons of the Shah Pahlavi regime, and finally lead to the overthrow of the monarchy. In the first part of the film, through a look at the life and struggle of three generations of Marjane’s family, we are introduced to a history of dictatorship, oil and dependency, rebellion and revolution, suppression and more rebellion.

Marjane’s childhood is marked by the figures of family members who struggled against the ruling system. Her mother’s father, born a prince in a vanquished dynasty, became a communist. Her uncle joined the Democratic Party of Azerbaijan, a party that supported the bordering then-socialist USSR and tried to create an autonomous region before it was crushed by the central government. Besides providing an outline of a certain historical period, this points to another truth: The fundamental contradictions in society constantly push some privileged intellectuals into rebellion against the system. They come to realize the outmoded nature of the dominant relations, and this understanding of the need to change the world and build another one on a whole new basis puts them in the ranks of the oppressed and even, at times, at the head of their struggles. More often than not, in Iran, we have seen such intellectuals lose their lives on this path.

Simple dialogues and pictures recount the bitter truth while ridiculing the tyrants and their cronies. This keeps an overly “educational” dust from settling on the film while at the same time engaging the spectator in history. Marjane is clearly not an average Iranian girl. She is from an intellectual family with a comfortable existence. But Persepolis is able to portray a universal reality (the history of a country) through the narrative of a particular and uncommon life. The history that is part of Marjane’s family heritage and shapes her life is part of the collective heritage that shapes the existence, hopes and dreams of all of us.

Pre-Marjane history is background for understanding her life, historical events that shaped our fate and played a not so insignificant role in shaping the world we are living in now: the Iranian revolution of 1979 and what came after. The overthrow of the monarchy leads to the rise to power of the Islamic Republic. Voice-over narration by the film’s main characters accompanies Satrapi’s drawings, pictures of waves of suppression, women being forced to cover their hair, arrests, escapes from the country and executions. The Islamic Republic attacks the revolutionary tide that brought down the Shah. Anoush, Marjane’s uncle, who was freed from the Shah’s prisons by the revolution, is arrested again. Marjane visits him in prison the night before his execution. He tells her of his belief in the final victory of the proletariat.

Pre-Marjane history is background for understanding her life, historical events that shaped our fate and played a not so insignificant role in shaping the world we are living in now: the Iranian revolution of 1979 and what came after. The overthrow of the monarchy leads to the rise to power of the Islamic Republic. Voice-over narration by the film’s main characters accompanies Satrapi’s drawings, pictures of waves of suppression, women being forced to cover their hair, arrests, escapes from the country and executions. The Islamic Republic attacks the revolutionary tide that brought down the Shah. Anoush, Marjane’s uncle, who was freed from the Shah’s prisons by the revolution, is arrested again. Marjane visits him in prison the night before his execution. He tells her of his belief in the final victory of the proletariat.

Earlier we saw the head-spinning and hopeful joy of the Iranian people in the first days of revolution when the anti-monarchy demonstrations had just started. We saw it reflected in little Marjane’s laughter while playing with her father. Now all that comes to an abrupt end. The execution of Anoush becomes a symbol of the defeat of the revolution. In a heartbreaking scene she rages against the god she imagines.

Marjane’s God

Here we are introduced to another of Marjane’s mental conflicts. Whenever she faces a problem that is not easily solved, or that she cannot even properly understand, Marjane turns to her god—an old white-bearded man who sits on clouds. He does not necessarily represent any particular religion. Since Marjane’s god, like other people’s, exists only in her mind, he is never really helpful. He just represents the wrangling between the known and unknown in her brain.

Early on, just after the revolution, on a neighborhood street, Marjane and other children chase a boy whose father is a member of the Savak, the Shah’s torturing secret police. But when she confronts him, she finds herself unable to hit him. Afterward, Marjane’s god tells her not to worry and to leave justice to him. In other words, the hope that the revolution will make things right is still in the air. Later, after Anoush’s execution, god appears again, but this time pleads weakness and says he is unable to do anything. Now the revolution has been defeated. Marjane rejects him, but this rejection is not permanent, as consciousness is not permanent and no decision is immune to wavering. The realities outside our mind interact constantly with our beliefs and our knowledge and lead to ups and downs in the developmental process of our life and thought.

This god makes another appearance much later in the film when, after failing in her attempt to find a new life abroad, Marjane is tired of life and wants to die. But now she is more experienced and aware of her role in change. And so Marx accompanies god in this scene. Marjane’s god, with his comic-book looks and voice, is one of the film’s many humorous touches, but at the same time reflects the wrangling of the human mind in the process of grasping reality.

The reality of the establishment of the Islamic Republic following the 1981 coup is brought to the screen through the faces of little girls wearing black veils. But this, however bitter, is only part of the reality. We also see the difference in the personalities of these little girls, portrayed with simple but lively lines that contrast sharply with the black cloth encircling their dynamic faces. A new force is rising from the depths of society. The rebellion of women and girls in the face of the Islamic Republic and its rotten old ideology is part of the fabric of the story, and the storyteller herself a symbol of this vibrant force.

The reality of the establishment of the Islamic Republic following the 1981 coup is brought to the screen through the faces of little girls wearing black veils. But this, however bitter, is only part of the reality. We also see the difference in the personalities of these little girls, portrayed with simple but lively lines that contrast sharply with the black cloth encircling their dynamic faces. A new force is rising from the depths of society. The rebellion of women and girls in the face of the Islamic Republic and its rotten old ideology is part of the fabric of the story, and the storyteller herself a symbol of this vibrant force.

Rebel in Vienna

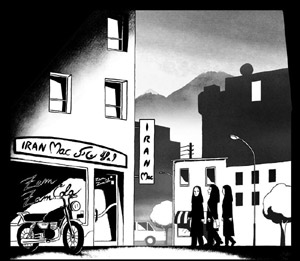

Marjane’s conflict with various representatives of the regime in the context of continuous repression brings her parents to send her abroad. Here we enter another episode of the movie: Marjane’s introduction to the West. She is sent to Austria and ends up living in a dormitory run by nuns. The nuns look – and act – like the Hezbollah Islamic thugs in Iran. Their faces are made ugly by the same sort of Khomeini frown habitually worn by the regime’s Pasdaran (Revolutionary Guards) and Basij (Islamic morality police). In Vienna, she experiences solitude, homesickness, racism, and at the same time, adolescence, the joy of first love and disappointment. A rebellious girl from Iran, Marjane finds herself most at home with the school outcasts, self-proclaimed anarchist, nihilist and other rebel classmates. Because they feel themselves in conflict with the authorities in a different form, they are fascinated by her stories of war and revolution. Some basic dividing lines in society are presented as different reactions in relation to this dark foreign girl—racism, misogyny and church on the one hand, and rebellion against the powers-that-be on the other.

It is worth mentioning that the film itself is a product of rebels from both the global “South” and “North.” Among those who encouraged Satrapi to publish her graphic novels (which have become very popular among comic fans) and her collaborators in making the movie (which despite fidelity to the novels has a life of its own) are European artists whose work is guided by criteria other than money and fame. Vincent Paronnaud, who worked closely with Satrapi in making the film, is a well-known graphic novelist himself, under the pen name Winshluz. He considers himself an “underground” artist and believes in trying to maintain an independence that means working with limited means but keeping freedom of thought and action. In an interview available on the Persepolis Web page, Satrapi says, “In many ways we are very different and even opposite, but we completed each other in making this film and showed that all the crap about East and West and cultural shock we are bombarded with is nonsense.” Considering the effect that Persepolis has had in the West, one can confidently say that the coming together of these two rebellious talents from East and West has put a dent in the walls the ruling order raises between people.

Marjane first experiences love in Austria—and ends up betrayed. Her broken heart, loneliness and homesickness make life so hard for her that she decides to return to Iran—the Iran of 1988, after the regime’s massacre of political prisoners, after the war with Iraq. Nearly a million people have been killed or crippled. Endless streets have been renamed after the dead, and a walk in the city is “a walk in a cemetery.” Marjane’s failure in Austria, combined with the grayness and the weight of death in Tehran, takes the force out of her. She starts thinking about death. It is here that god (and Marx) come to her and tell her to be brave. Marx cheerfully emphasizes that the struggle continues. Marjane decides not to give up hope. She gets up and puts her decision to practice. She takes exams, goes to university and starts yet another episode of her life.

Marjane first experiences love in Austria—and ends up betrayed. Her broken heart, loneliness and homesickness make life so hard for her that she decides to return to Iran—the Iran of 1988, after the regime’s massacre of political prisoners, after the war with Iraq. Nearly a million people have been killed or crippled. Endless streets have been renamed after the dead, and a walk in the city is “a walk in a cemetery.” Marjane’s failure in Austria, combined with the grayness and the weight of death in Tehran, takes the force out of her. She starts thinking about death. It is here that god (and Marx) come to her and tell her to be brave. Marx cheerfully emphasizes that the struggle continues. Marjane decides not to give up hope. She gets up and puts her decision to practice. She takes exams, goes to university and starts yet another episode of her life.

If god represents Marjane’s struggle to understand reality, Grandma plays the role of experience and consciousness. She is a colorful major presence throughout the movie, full of experience, yet cheerful and good-humored in her scathing ridicule of everything she feels is wrong. She curses freely and every morning picks jasmine to put in her bra “to smell good.” She teaches Marjane to preserve her integrity. Wherever Marjane turns her back on her values out of weakness or fear (whether in the face of racism in Austria or the Pasdaran in Iran), Grandma emphasizes the importance of perseverance in one’s principles, since she has seen and knows that human beings, even in the hardest of situations, have choices.

If god represents Marjane’s struggle to understand reality, Grandma plays the role of experience and consciousness. She is a colorful major presence throughout the movie, full of experience, yet cheerful and good-humored in her scathing ridicule of everything she feels is wrong. She curses freely and every morning picks jasmine to put in her bra “to smell good.” She teaches Marjane to preserve her integrity. Wherever Marjane turns her back on her values out of weakness or fear (whether in the face of racism in Austria or the Pasdaran in Iran), Grandma emphasizes the importance of perseverance in one’s principles, since she has seen and knows that human beings, even in the hardest of situations, have choices.

Posing Important Questions

This film poses important questions in relation to revolution. Questions that it does not necessarily answer, but which, when posed, trigger thinking and demand analysis. In one scene, a member of Marjane’s family is ill and needs heart bypass surgery, an operation not possible in Iran. In order to stay alive he needs permission to leave the country. His wife goes to the administrative head of the hospital to ask for permission. The new boss used to be the janitor in her building before the revolution. He has become a strict Moslem, grown a beard, doesn’t look women in the eye… and of course refuses permission to leave. The patient’s fate, he sighs, “is up to the will of god.” The scene makes us deeply feel the impotence of people in the face of the new reactionaries in power, and the rule of ignorance and superstition against science, logic and the interests of the people.

This character points to one of the political and ideological questions every revolution faces. Revolution upsets the old relations and opens the way for creating new relations. But when the leadership is in the hand of forces whose interest is in preserving the old order in a new form, as was the case in 1979 Iran, backward tendencies among the people can be reinforced and turned into a tool in the hands of the new ruling class. One of these tendencies is to use the opportunities provided by the situation to pull oneself up and try to grab posts that were not previously reachable. At times such a tendency among the lower strata is linked with a feeling of revenge against those who had privileged positions in the past; and such violence often targets not the ruling classes, but the educated middle strata. It is clear that without a fundamental change in the existing relations, only a handful (who usually happen to have sharp opportunistic noses) get anywhere, and the great majority continue to be looted and suppressed. The Islamic Republic, which has used every reactionary ideological resource, most importantly religion, to stupefy the people and establish and preserve its rule, took advantage of this backward tendency to keep a populist facade and maintain its base among a section of the masses. The result was vicious suppression of intellectuals and the masses.

Persepolis, in its own way, thoroughly exposes the crimes of the Islamic Republic. But despite what some choose to assume, it does not overlook the role of the West in bringing puppet tyrants to power and suppressing the people. Viewers become aware of the role of Britain in the coup that brought the father of the Shah to power, the pillage of the country’s oil, the training of Savak torturers by the CIA, and the sale of arms by Western countries to both sides in the Iran-Iraq war. These are all reminders that Iran does not exist in a vacuum but is a part of a system that has spread its tentacles throughout the globe and that the struggle there is part of the struggle against that global system.

Persepolis, in its own way, thoroughly exposes the crimes of the Islamic Republic. But despite what some choose to assume, it does not overlook the role of the West in bringing puppet tyrants to power and suppressing the people. Viewers become aware of the role of Britain in the coup that brought the father of the Shah to power, the pillage of the country’s oil, the training of Savak torturers by the CIA, and the sale of arms by Western countries to both sides in the Iran-Iraq war. These are all reminders that Iran does not exist in a vacuum but is a part of a system that has spread its tentacles throughout the globe and that the struggle there is part of the struggle against that global system.

Lines Drawn by Hand

This film is a valuable work of art. Its minimalist form seems to be the best way to tell a story so full of events and major issues. The brevity of words, simplicity in drawings, and economy in color, tell a compact story full of humor and subtlety in an hour and a half. What in another context could be considered artistic weaknesses, like the simplicity or at times even crudity of the lines, the lack of color and the plain straightforwardness of text, are all strengths in Persepolis. Explaining why the film was made with traditional hand-drawn cells (individual animated picture drawings) instead of computer-generated graphics, Satrapi says, “Lines in computer-generated graphics are flawless. This takes the personalities out of the characters, human beings are not perfect, and the lines drawn by hand better reflect their souls.” But anyone familiar with traditional animation methods knows what a gigantic effort it takes to produce a one-and-a-half-hour film with 12 pictures a second. This film is the product of many artists working over the course of three years, from Chiara Mastroianni, Catherine Deneuve, Danielle Darieux and Simon Abkarian, whose voices gave further life to the characters, to all those behind the scene who were busy drawing, adding music, editing, etc.

Satrapi and Paronnaud have taken the contradiction- ridden life of a girl from a country shaken by revolution and mired in war, a world full of love and walls, and turned it into a fine work of art. And thus they have brought the people of both sides of the divide (between the oppressed and oppressor countries) closer. In an interview Satrapi says, “If we don’t look at people as humans, we can bombard them and nothing happens. Every day hundreds of people are killed in Iraq and we have not even observed a minute of silence.” For years the imperialist ruling classes—with the witting or unwitting help of the Islamic Republic of Iran of course—have been portraying the people of Iran and the Middle East as nothing but Moslem fanatics, an unreal picture that prepares Western minds for murder on a mass scale. Today this black and white animation portrays the Iranian people more realistically than many articles and discourses. Viewers see that despite the rule of death over the country, people celebrate life in its many forms, even if it means they will get in trouble for putting on lipstick or lose their life for partying. Nothing brings people closer together than real knowledge of each other’s situation, problems and dreams. Satrapi, in her interview, adds, “If people come to the film and say these people are humans like us, the film is successful.” The extraordinary enthusiasm of people in France for the film (which will soon be available in English) is a sign of its success.

Postscript

The power of Satrapi’s art has won support from influential people, including two of France’s most internationally famous women actors, and that in turn has helped get the film into mainstream channels. It has brought in over a million viewers since it opened there in late June, with an equally wide impact on French-speaking audiences in Belgium and Switzerland. Spanish and Portuguese-subtitled versions are attracting a following in Europe and some Latin American countries. It will play in German theatres beginning in November.

An English version is planned for North American release December 25. Several women in Hollywood waged a personal crusade to get it made, including a producer of Steven Spielberg films and the daughter of a top executive at Sony Pictures, which recently bought distribution rights. An English-language version is considered key for broad national distribution beyond the art houses where subtitled films are often confined in the U.S. Catherine Deneuve and Chiara Mastroianni, who also lent their voices for the French version, are to be joined by Sean Penn, Gena Rowlands and Iggy Pop. A French film industry commission picked this black and white animated film as its representative in the Hollywood Oscar competition for the “best foreign film” award.

For the Spanish trailer, vertigofilms.es/persepolis.

For the English, www.sonyclassics.com/persepolis.

Also in French and English on youtube.com. Satrapi’s Web page in French is on http://www.myspace.com/persepolislefilm

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.