Revolution #241, July 31, 2011

From a reader:

Long Suppressed Photos on Exhibit

from the U.S. Nuclear Attack on Japan

|

By 1945, World War 2 had devastated Europe and the Pacific. More than 20 million people in the Soviet Union alone had been killed in this war. On February 13, 1945, U.S. allies firebombed the German city of Dresden, 135,000 people were killed. Then on August 6, a U.S. Air Force plane dropped the world’s first nuclear bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. They killed an estimated 140,000 people. Three days later they dropped a nuclear bomb on Nagasaki, killing 74,000 people.

Between 1945 and 2002, around 100,000 nuclear bombs were built. Today, according to the Obama administration, the U.S. nuclear arsenal holds over 5,000 weapons. The U.S. continues to expand and maintain its power in the world by threatening to use these weapons.

Why is the impact of the U.S. nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki not seared into our minds today?

In New York City a small but very powerful exhibit of photos gives a cold, hard glimpse into this horror: “Hiroshima Ground Zero 1945” at the International Center of Photography (ICP). This exhibit not only shows photos never before made public of the nuclear terror rained down on the people of Japan and a sense of the threat that this arsenal holds today, but the story of how this exhibit came about gives an idea, at least in part, as to how and why this outrage is just not a part of our consciousness today.

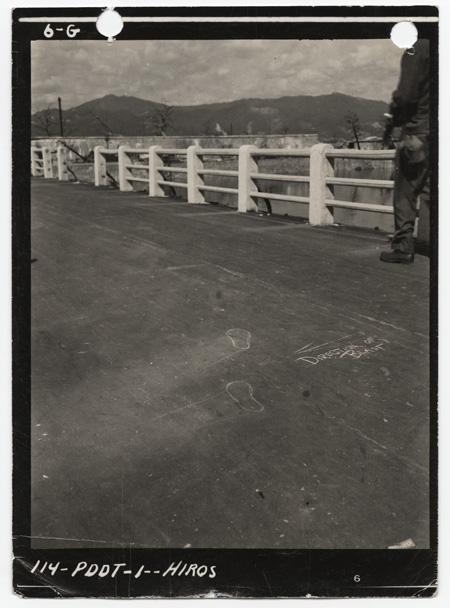

On exhibit are the once-classified postcard-size prints of photos of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division, the group of 1,150 military personnel and civilians, including photographers, sent to record the destruction. You can see from the notes made by those involved that the purpose of this survey was to evaluate the destruction of the blast and determine what kind of structures and materials could withstand a nuclear holocaust and apply this to developing policies for constructing bomb shelters, promoting suburbanization and improving construction materials and practices to better ensure the survival of the U.S. in a nuclear war.

The photos show the annihilation of Hiroshima, flattened out with the wrecks of just a few twisted structures left as far as the eye can see; most of it is just indistinguishable rubble. It takes a while to realize what is missing. People. It was a huge city, but you don’t see anyone. The captions from the photos tell only the story of what is useful to the imperialists: “Honkara Grammar School. Looking south along corridor of third story showing portal construction and buckling of panel wall. Note cracking of roof panel. Also destruction of combustable floor, partitions and content by fire.” Content. That would mean books, chairs...and children. There are a few photos that hint at what this means to people. One, a schoolboy’s jacket on a chair. Others, ghostly shadows burned onto a wall, the imprint of the rubber soles of someone’s shoes that kept the asphalt on that spot of a bridge from burning, no other hint of the person.

After these cities were destroyed, the U.S. government confiscated all photos of what happened and restricted their circulation. No images were to be published “which might, directly or by inference, disturb public tranquillity.” It was years before Life magazine published a few photos. The photos shown in this exhibit are part of a collection of 700 that had been held by Robert L. Corsbie, an executive officer of the Physical Damage Division who died in a house fire in 1967. They were left in a basement for over 40 years before being acquired by the ICP in 2006.

What has become clear is that unleashing nuclear warfare on Japan was not, as touted, some kind of supreme act of mercy to end the war in the Pacific once and for all. It was a cold, calculated, murderous move to claim position of world superpower. From the very beginning it was an experiment on how to continue waging war:

- Two bombs were dropped, one plutonium, the other uranium to evaluate the weapons’ effectiveness.

- The target cities had almost no military significance, they were outstanding mostly because they had sustained very little previous damage from the U.S. bombing of Japan during the war, they would be easier to assess damage done exclusively by the nukes.

- The cities’ geology, especially Hiroshima being surrounded by mountains, contained the blasts and their victims.

- The bombs detonated high in the air to maximize death and minimize structural damage.

- The military and civilian teams, such as the Manhattan Project Atomic Bomb Investigating Group, set up in advance to move in as soon as Japan surrendered, to survey their destruction. Along with the data collected and the documenting of images of the aftermath confiscated, medical intelligence was also seized and classified “top secret.”

After visiting the show, my friend from Japan and I were talking about the nightmare unfolding around the Fukushima nuclear reactors leaking radiation caused by the recent earthquake in Japan. One would think, after the devastation of the war and the generations of Japanese suffering from the horrible effects of radioactive contamination, that there would be some real expertise in dealing with such disasters, but the legacy of the strategy of confiscating and suppressing knowledge of this destructive power, including medical treatment records, continues this bloody history.

The exhibit is at 1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd St., New York, NY, on view through August 28. The website for the exhibit includes many of the photos: icp.org/museum/exhibitions/hiroshima-ground-zero-1945.

Recently I was reading an essay called “Disarming Images” about an exhibit of art for nuclear disarmament which was held in the early 1980s. And I noticed that the author of this essay points out that according to the dictionary, Webster’s Third International Dictionary, the name “bikini” given to the bathing suit comes from comparing “the effects of a scantily clad woman to the effects of an atomic bomb.” When you think about this, and you think about the horrendous death, destruction, mutilation and suffering alive before dying that was caused by the atomic bombs that the U.S. dropped on Japan, and what would result from the much more powerful nuclear weapons these monsters have today—when you think about all that, and you think about the reasons for naming the bikini after all that, and what kind of view of women this promotes—do you need any other proof about how sick this system is, and how sick is the dominant culture it produces and promotes? Bob Avakian, BAsics 1:17 |

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.