You Don't Know What You Think You "Know" About...

The Communist Revolution and the REAL Path to Emancipation:

Its History and Our Future

Interview with Raymond Lotta

Updated April 30, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Editors' note: This interview and "The REAL History of Communism" timeline have been updated from the versions that originally appeared at revcom.us, to be consistent with the new expanded eBook version. The eBook is available from Insight Press.

Contents

No Wonder They Slander Communism

by Bob Avakian

Interview with Raymond Lotta

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: The First Dawn—The Paris Commune

Marx Draws the Essential Lesson from the Commune: We Need a New State Power

Chapter 3: 1917—The Revolution Breaks Through in Russia

Lenin and the Vital Role of Communist Leadership

Radical Changes: Minority Nationalities

Constructing a Socialist Economy

Changing Circumstances and Changing Thinking

A Turning Point: The Revolution Is Crushed in Germany and the Nazis Come to Power

Two Different Kinds of Contradictions

A Crucial Relationship: Advancing the World Revolution, Defending the Socialist State

Chapter 4: China—One Quarter of Humanity Scaling New Heights of Emancipation

China on the Eve of Revolution

Mobilizing the Masses to Transform All of Society

An Unsettled Question: What Direction for Society?

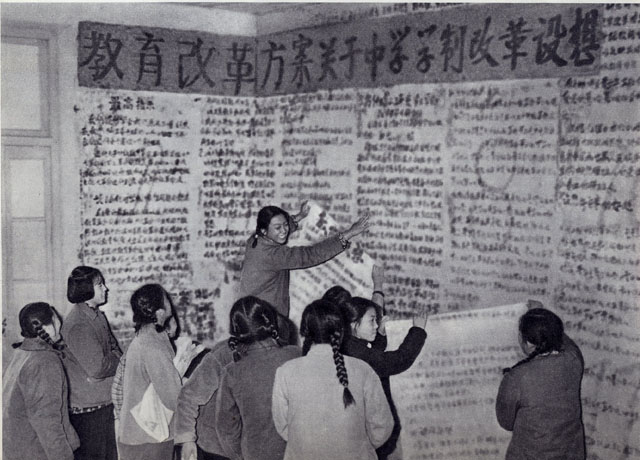

The Cultural Revolution: The Furthest Advance of Human Emancipation Yet

The Danger of the Revolution Being Reversed

Unleashing the Youth to Initiate the Cultural Revolution

The Contradictory Nature of Socialism

Mass Debate, Mass Mobilization, Mass Criticism

“Human Nature” and Social Change

Sending Intellectuals to the Countryside

Chapter 5: Toward a New Stage of Communist Revolution

Bob Avakian Brings Forward a New Synthesis of Communism

Notes

Appendix: Two Essays Concerning Epistemology

“But How Do We Know Who's Telling the Truth About Communism?”

A Reader Responds to “What’s Wrong with ‘History by Memoir’?”

Chapter 1: Introduction

People need the truth about the communist revolution. The REAL truth. At a time when people are rising up in many places all over the world and seeking out ways forward, THIS alternative is ruled out of order. At a time when even more people are agonizing over and raising big questions about the future, THIS alternative is constantly slandered and maligned and lied about, while those who defend it are given no space to reply. It is urgent that the questions be answered, and the TRUTH be told about the communist revolution—the real way out of the horrors that people endure today, and the even worse ones they face tomorrow. To do this, Revolution newspaper arranged for Raymond Lotta to be interviewed by different groups of people in different parts of the country, and other people sent in questions. What follows is a synthesized, edited version that draws on those interviews and adds new material since the interviews were first conducted.

Question: I’ve heard you talk about the “first stage” of communist revolution. What exactly are you referring to?

Raymond Lotta: We’re talking about a sea change in human history, the first attempts in modern history to build societies free from exploitation and oppression. Specifically, we’re talking about the short-lived Paris Commune of 1871, the Russian revolution of 1917–1956, and the Chinese revolution of 1949–1976. These were titanic risings of the modern-day “slaves” of society against their “masters.” They aimed to bring about a community of humanity, a society based on the principle of “from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs,” and one where there are no more divisions among people in which some rule over and oppress others, robbing them not only of the means to a decent life but also of knowledge and a means for really understanding, and acting to change, the world.

Never have there been such radical and far-reaching transformations in how society is organized, in how economies are run, in culture and education, in how people relate to each other, and in how people think and feel as there were in these revolutions. Against incredible odds and obstacles, and in what amounts to a nanosecond of human history, these revolutions accomplished amazing things—and they changed the course of human history. Never before had the myth of an unchanging human nature—in which people are “naturally” self-seeking, and some people just “naturally” dominate others—been so decisively exploded.

For those few decades, a better world seemed on the verge of birth. As it is put in Communism: The Beginning of a New Stage, A Manifesto from the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA, for the first time, the “long night... the thousands of years of darkness for the great majority of humanity”—where society is divided into exploiter and exploited, oppressor and oppressed—this was broken through, and a whole new form of society began to be forged.1

The Lies of Conventional Wisdom

Question: But the conventional wisdom is that these revolutions were not liberating, but extremely autocratic, trampling on the rights of people... utopias turned into nightmares.

RL: Yes that is the conventional wisdom, and it is built on systematic distortion and misrepresentation... built on wholesale lies as to what these revolutions were about: what they actually set out to do, what they actually accomplished, and what real-world challenges and obstacles they faced.

Now people have a certain awareness of how they have been systematically lied to about things like “weapons of mass destruction” that were the pretext for the war in Iraq. And we’re not talking about incidental mis-admissions of fact here... the Iraq war resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, and the dislocation of millions.

But all too many people who consider themselves “critical minded” are all too willing to accept the “conventional wisdom” on communism. And let me be clear, the ruling class and intellectual guardians of the status quo have been engaged in a relentless ideological assault against communism... through popular journalism, so-called scholarly studies, memoirs that traffic in the “authenticity of personal experience,” films, and so on.

You know, for several years, I have been engaged in a project called “Set the Record Straight,” taking on these distortions and bringing to people the actual truth of these revolutions. For example, back in 2009–2010, I was on a campus speaking tour and one thing we did was to set up tables on campuses with a “pop quiz” on just basic facts about the communist revolutions.2

And the students scored terribly on the quiz. That is shameful, not just because it’s a statement on higher education... but more importantly because people are being robbed of vital understanding of how the world could be radically different, could be a far better place, where human beings could really flourish.

There are real stakes here, real relevance and urgency to this now.

We Need Revolution and a Whole New World

Question: What do you mean by “stakes”?

RL: Look at the state of the world... the unjust wars, the poverty and savage inequality, the unspeakable oppression and degradation of women. The environmental crisis is accelerating and nothing is being done to stop it. The capitalist-imperialist class in power... that holds and violently enforces that power... that controls the world economy and the world’s resources... this class and the system it presides over have put us on a trajectory that is threatening the very eco-balances and life-support systems of the planet.

People are responding, especially the new generation. We’ve seen major stirrings of protest and rebellion: the massive uprising in Egypt of 2011, the Occupy movements, the defiance of youth in Greece and Spain, the recent outbreaks in Brazil and Turkey. People are standing up. People are searching and seeking out solutions and philosophies. Various political programs and outlooks have gained influence and followings: “leaderless movements,” “real democracy,” “anti-hierarchy,” “anti-statism” and “horizontalism,” “economic democracy,” and so on.

But the one solution that is dismissed out of hand is communist revolution. Yet it is precisely and only communist revolution that can actually deal with the problems of society and the world that people are agonizing about... and that can realize the highest aspirations that have brought people into the streets.

And we are seeing the price of what it means where there is no communist leadership, vision, and program.

Take Egypt. People heroically toppled the Mubarak regime. On the surface there was dramatic change. But the military representing imperialism remains in power, and people are locked into the vise-grip of two unacceptable alternatives: Islamic fundamentalism, or some variant of Western democracy serving imperialism. The notion of a “leaderless” movement that can somehow produce fundamental change has shown itself to be a dangerous and deadly liability and delusion.3

Question: But people say that Lenin and Mao just took power for a small group. How do you answer that charge?

RL: Lenin4 in 1917 in Russia, and then Mao5 in China led parties that in turn led millions and then tens of millions of people in revolutions that went after the deepest problems of society. They applied and developed the theory of scientific communism first brought forward by Karl Marx.6 This science lays bare the source of the exploitation and misery in society—the division of society into classes in which a small group monopolizes the wealth and controls society on that basis. And it shows how all that could be fundamentally overcome and uprooted, with a revolution corresponding to the interests of, and involving as its bedrock base, the exploited class of today: the proletariat.

The parties forged and led by Lenin and Mao did two things. First, they led the masses to make revolutions... to overthrow the old system. Second, they led people to establish new structures that empowered the masses to begin to take responsibility for ruling society and transforming it... beginning the process of abolishing all relations of exploitation and oppression and all the institutions and ideas that correspond to and reinforce those relations.

Marx had uncovered the possibility of a new emancipatory and liberating dawn for humanity. He insisted that this would ultimately have to be the work of the masses themselves. And these revolutions gave living expression to that.

At the same time, you couldn’t do this without leadership—scientific and far-seeing leadership. And this lesson was paid for in blood in the first great attempt at revolution—the Paris Commune.

Chapter 2: The First Dawn—The Paris Commune

Question: Could you say more about the Paris Commune?

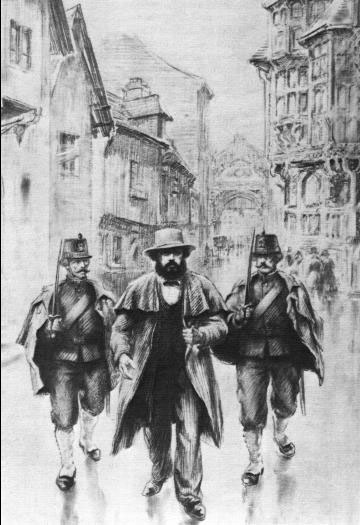

Raymond Lotta: The Paris Commune happened in 1871, during the last days of a war between France and Germany. The people of Paris had been suffering terribly... massive unemployment, food shortages, and the destruction of war. On March 18, they rose up against their “own” government. The Paris National Guard, which had radical influences within it, revolted... and sections of the city joined in an insurrection. The Guard took over the town halls of most of the districts of Paris, and executed two generals of the French wartime government.

A week later, the National Guard organized new municipal elections. A new government was created. This was the Commune. It was made up of socialists, anarchists, Marxists, feminists, radical democrats, and other trends.

Right away, the Commune abolished the old police force. It introduced radical social reforms: separation of church from state; it made professional education available to women and gave pensions to unmarried women; and it canceled many debts. The Commune established centers where the unemployed could find work. And the Commune allowed trade unions and workers’ cooperatives to take over and run the factories that the capitalists had abandoned during the war. Immigrants were allowed to become full citizens.

But it wasn’t just that a new government was taking progressive measures. There was an attempt to create a new mode of rule, a different kind of governing system.

Question: What do you mean by that?

RL: The Communards, as they were called, tried to create a political system representing the interests and needs of the workers, urban poor, and lower classes in society... those who had been long oppressed and denied political power. And they also set out to create a form of rule that operated differently from the bourgeois system. They tried to make administrators more accountable to the people who elected them; they tried to simplify government and link it more directly to the rough and tumble of the masses’ lives.

Question: I’ve met anarchists who say they base themselves on the Paris Commune—that this is their model. What would be wrong with that?

RL: Well, there were a few problems, but one big one. The Communards had gotten this going in Paris—and it was really remarkable what they were doing—but they had not decisively overthrown the old exploiting order and thoroughly destroyed the old state power. In fact, the top political leaders and the military forces of the old French government had fled to the outskirts of Paris, to an area called Versailles.

You see, the central committee of the Commune conceived of what they were doing as a municipal revolt and that they could hold out in Paris. The Communards had this idea that by creating the Commune... that this model, with its creativity in the now liberated space of Paris, would be the example for the rest of the country to follow. But this was not a correct understanding.

The French ruling class was not reconciled to its initial defeat, and it still had the power to enforce its will... notably regular armed forces.

By May, this reactionary Versailles government had amassed an army of 300,000 soldiers. On May 21, the army reentered Paris to crush the Commune. The Communards fought back heroically. But the military forces plowed through their street barricades and went on to massacre between 20,000 and 30,000 Parisians... just over the course of one week. There was a famous last stand, in a cemetery, with people literally backed to the wall. A wave of executions followed.7

Marx Draws the Essential Lesson from the Commune: We Need a New State Power

Karl Marx enthusiastically supported the Commune. After its defeat, he scientifically assessed its significance and lessons. He pointed out that the Commune was positively prefiguring a new kind of state, the dictatorship of the proletariat—that the Communards were not simply laying hold of the old state machinery and trying to put it to progressive use. But he also pointed out that one of the Paris Commune’s fatal weaknesses was that it did not march on Versailles and thoroughly shatter and dismantle the old state machinery, as concentrated in the permanent army of the old order. He also pointed out that the Commune failed to dismantle and seize the assets of the Bank of France, which was financing the regroupment of the old regime and its military in Versailles.

Marx showed that every state was, in its essence, a dictatorship of the dominant class in society. That is, there may be some forms of democracy, but so long as society is divided into classes, the army, police, courts and executive power will enforce the interests of the dominant class—which today means the capitalist-imperialist class. Again, a key lesson of the Commune was that the capitalist state power has to be thoroughly smashed and dismantled... it has to be replaced with a new system of state power, the dictatorship of the proletariat. In other words, you have to dismantle the armed forces of the old system—and to establish a whole new economic and social system, you have to create a new state power that can enforce the will of the oppressed and exploited.8

And the Commune had another weakness: it did not have the necessary leadership to analyze, confront, and act on the real challenges it faced. It did not have a leadership basing itself on a scientific understanding of what it would take to defeat counter-revolution and what it would take to go on to transform society... you know, to forge a new economy and social system.

The Commune was this inspiring and world-historic breakthrough for oppressed humanity. In that fleeting moment of the Commune was the embryo of a communist society without class distinctions and social oppression.9

It was Lenin who applied the lessons of the Commune and led the Russian revolution that created the world’s first socialist state.

Less than 50 years after the defeat of the Commune, a far more sweeping and deep-going revolution takes place... in Russia. As I was just saying, Lenin was summing up lessons of the Commune, and developed the understanding of the need for vanguard leadership. Because the fact of the matter is... a key reason that the Commune couldn’t make good on its incredible potential was because of the absence of unified leadership. Some people say that was the great thing about the Commune. But the absence of leadership was one of the reasons that they got crushed... and that’s not a great thing!

Question: But what you’re saying goes against this whole view—I’m thinking about the kinds of movements that you pointed to, like Occupy—that highly organized leadership suffocates people.

RL: Yes, that’s out there, big time, and it’s profoundly wrong. Lenin developed the scientific understanding of the need for a vanguard party based on two critical insights. One, the masses of people cannot spontaneously develop revolutionary consciousness and scientific understanding of how society is structured and functions and the ways, the only ways, it can be radically transformed... from their own daily experience and struggle. Look at Egypt. People have been truly courageous in standing up, but you have all these illusions about the Egyptian military. You need leadership to bring this understanding to the masses of people. On the basis of this understanding, masses can be unleashed to consciously transform the world—and this is part of what has been proven by the history we’re going to get into. Making revolution requires science. Revolution requires passion, heart, courage, and creative energy. But that won’t change the world in and of itself... without a scientific grasp of what it takes to make revolution and emancipate humanity.

Question: And the other point?

RL: The need for centralized leadership. To actually enable the masses to break through the obstacles and what the enemy is going to throw at you, not least its military strength. And to be able to navigate through all the twists and turns, including the maneuvering and deceptions of the ruling class in a revolutionary crisis, and to lead people to actually overthrow the old order and to go on to revolutionize society. You need a strategic approach and the strategic ability to marshal all the creativity and resolve of the masses. When people do break free of “normal routine” and lift their heads, where is this all going to go? The question of leadership is decisive. And, look, there is no such thing as “leaderless-ness.” Some program and some force, representing different class interests, is going to be leading, no matter how much people might want to shun leadership. And let’s be honest: “leaderless-ness” is actually a program that is being led—and it doesn’t lead anywhere radically transformative.10

You need centralized leadership. How are you going to coordinate an uprising when conditions change and the opportunity emerges? How are you going to coordinate the rebuilding of society following the destruction of revolutionary war? How are you going to coordinate the functioning of a new economy? How are you going to coordinate support for world revolution? You need centralized leadership.

Now Lenin wasn’t arguing, “Well, we’ll just substitute ourselves for the masses.” No, the whole point is that the more that leadership plays its vanguard role, the greater is the conscious activism of the masses. The masses make history, but they cannot make history in their highest interests without leadership. Having that leadership is why the Russian revolution took place and changed the whole course of world history.

Chapter 3: 1917—The Revolution Breaks Through in Russia

Question: So, let’s get into the Bolshevik revolution and the conditions of Russian society. In most schools, they don’t even teach the basic facts.

Raymond Lotta: It’s called the Bolshevik revolution, because the communist party was originally called Bolshevik (the word meaning “majority,” referring to the majority of forces grouped around Lenin who resolved to forge a party of revolution).

The Russian revolution took place in the turmoil of World War 1. The war started in 1914 and lasted until 1918. This was a war in which two blocs of imperialist great powers fought each other. One bloc included Great Britain, France, and the U.S. (and Russia was part of this alliance); and the other was led by Germany with its allies. They were fighting for global supremacy, particularly control over the oppressed colonial regions of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

This was monstrous, mechanized, modern war. Combatants were gassed, torpedoed, mined, bombarded by unseen artillery, machine-gunned. Slaughter on a scale unseen before in human history... 10 million dead, and another 20 million wounded.11

When Russia entered the war, all the major parties in Russia and most of the major parties in Europe supported the war in the name of patriotism... all except the Bolshevik Party led by Lenin. It took an internationalist stand, training people to see how this war was not in the interests of oppressed humanity and calling on people in the imperialist countries to rise up in revolution and defeat their own governments.

Most of Russian society at the time was made up of peasants. They had small plots of land that many of them worked on (almost like sharecroppers of the South in the U.S.). Conditions were very backward and people were locked into tradition. Peasants planted seed according to the religious calendar. Women faced horribly oppressive conditions.

The cities were places of crowded housing and disease.

Russia was an empire. The dominant Russian nation had colonized areas and regions of Central Asia (like Uzbekistan), and it also subordinated more developed areas like Ukraine. Russia was called “the prison-house of nations.” Non-Russian nationalities made up about 45 percent of the population, but minority cultures were forcibly suppressed and their languages could not be taught or spoken in schools.

Russia was an autocratic, repressive society. The Tsar relied on secret police, jails, and surveillance.

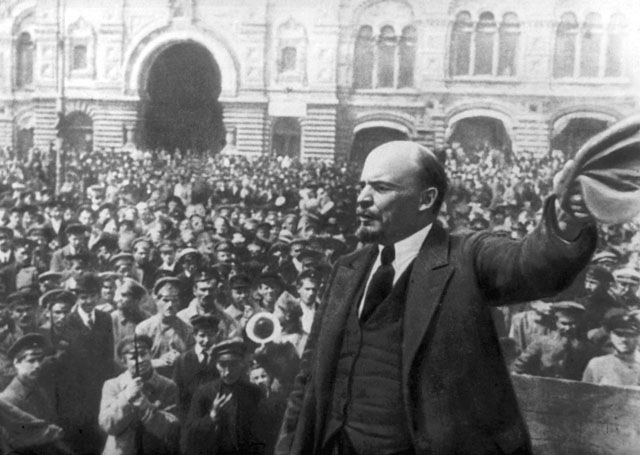

World War 1 intensified all the suffering in society. Some 1.5 million Russians died in the war, and three million were wounded. People were going without food. The war set off a “crisis of legitimacy” in Russian society... and a revolutionary climate took hold. Workers rioted and struck for better conditions. Women took the streets. Many soldiers refused to suppress the protests, and mutiny spread. The Tsar was overthrown.12

But the new government did nothing to change the fundamental conditions facing the masses of people... and it made secret deals with the British and French imperialists to keep Russia in the war.

Lenin and the Vital Role of Communist Leadership

Question: But it’s often said that the Bolsheviks were scheming behind the scenes and basically staged a coup in October 1917.

RL: Nonsense. The Bolshevik Party led by Lenin was prepared to act and lead as no other force in Russian society was. It had grassroots strength and organization in factory committees, in the armed forces, in the soviets. These were the illegal, anti-government representative assemblies of workers contesting for power in the big towns and cities....

The Bolshevik program and vision resonated widely and deeply in a society in crisis, upheaval, and looking for direction. The Bolshevik Party led the masses of people to see through the various maneuvers of this new regime. It formulated demands for “land, peace, and bread” that spoke to overriding needs in a situation of horrible suffering and privation—but which no other party would speak to. And in October, Lenin and the Bolsheviks led the masses in an insurrection. This was the October Revolution.13

Question: But, again, the way it’s told, the Bolsheviks were just tightening power for themselves.

RL: Look, a new state power was being created. Immediately, the new government issued two stunning decrees. The first decree took Russia out of the war and called for an end to the slaughter, and called for a peace without conquest or annexation. The second decree empowered peasants to seize the vast landholdings of the tsarist crown, the aristocratic landholding classes, and the church (which itself owned large tracts of land).

But there was a larger significance to what was happening. That “long dark night,” that darkness of exploitation and oppression, was being broken. For the first time since the emergence of class society, society was not going to be organized around exploitation. And this reverberated around the world.

In Europe, soldiers, sailors, and workers exhausted by the continuing war followed the news of what was happening in the new society. In Germany, in Kiel and Hamburg, rebel sailors of the German navy mutinied against orders to continue the war. In 1918, insurrections broke out in parts of Central Europe, and were viciously suppressed. There were many countries in Europe where revolutionary situations emerged, and in some revolutions took place. But nowhere else, other than in Russia, did revolution break through and hold on. A big part of the reason was that there was no genuine vanguard party in these societies. But because of the influence of October, new communist organizations spread to different parts of the world. And the Bolsheviks took the standpoint of spreading revolution, and promoted Marxism and vanguard party organization. On this basis, a new international body that coordinated the activity of communist parties and organizations around the world was formed—a tremendous advance for the revolution.

World capitalism would never be the same. World history had been profoundly changed.

Question: You’ve painted a picture of who supported the communist revolution in Russia. And why. But didn’t some people bitterly oppose this revolution?

RL: Yes. There was civil war between 1918 and 1921. The country was thrown into a state of near chaos and collapse.

Just a few short months after the 1917 insurrection, reactionary forces inside of Russia, representing the old overthrown order, launched a counter-revolutionary assault against the new regime. Fourteen foreign powers, including the U.S., intervened with troops and military assistance to support the counter-revolution. You know, in October 1918, when the first anniversary of the Revolution was being celebrated, three-quarters of the country was in the hands of counter-revolutionary forces. Think about that.

The new proletarian state was isolated internationally, and there were acute shortages of food and armaments.14

Here you can see the vital role of vanguard leadership. The Party took responsibility to coordinate military activity. It developed economic policies to meet social needs and hold society together. It led in creating new social institutions. The revolutionary press and other means of communication spread Marxism and the socialist vision of a new economy, new political institutions, and new values. This ignited a whole new emancipatory “discourse” in society—and this was a very powerful and positive mood-creating factor.

The new society was facing international onslaught. Yes, the economy was on the verge of collapse at times, and people were suffering. But communist leadership held strong and set out to expand and solidify and mobilize the base among those who wanted to hold on to liberation with everything they had. And people could mobilize and stand up because there were now new organs of proletarian state power that expressed their will and determination.

A New Kind of Power

Question: What do you mean by “organs of proletarian state power”?

RL: That’s a good and central question. In capitalist societies, the armies, the courts, the police, the prisons, and—at the very top—the executive branch all serve the capitalists. These organs repress the people when they stand up—take what was done to Occupy, for instance—or even before they stand up, just so they “know their place” in capitalist society—like in stop-and-frisk, in New York and other cities. The legislatures are just talking shops, places to enable the different competing capitalists to wrangle out their disagreements and/or to serve as harmless safety valves for mass discontent. So you could say that those are organs of reactionary state power, or organs of bourgeois—that is, capitalist—state power. Like I said earlier, it’s a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, or capitalist class.

The socialist revolution has to set up new, revolutionary organs of power representing the proletariat. These organs of power, which should, over time, involve increasing numbers of people from both the bedrock of society and more middle class sections too, have to be able to suppress the counter-revolution. For instance, you need public security forces—but on a completely different basis, serving completely different ends, and behaving in a completely different way than what we have today. But these new organs of power also have to be able to back up the people in making transformations in every sphere, leading them and enabling them to organize their efforts in creating a whole new society on a whole new basis. This is what is meant by dictatorship of the proletariat.

The masses forged new practices in the really dire situations of all-out civil war. For instance, there was the practice of cooperative voluntary labor, where people came together to maintain sanitation and hygiene of the cities under terrible duress. People were changing human nature, pitching in together and forging new relations based on cooperation. And the new state was giving this backing.

Question: You never really hear about this civil war when the revolution is being referred to. What actually happened?

RL: The counter-revolution was defeated at great cost. One million people died in the fighting and three million more died of disease during the Civil War. Nine-tenths of the engineers, doctors, or teachers left the country. Some of the most dedicated worker-communists were killed on the front lines. And the working class itself was vastly reduced in size—by the fighting and by the dislocation and destruction, with people fleeing to the rural areas.

Bourgeois commentators act as though the Bolsheviks were taking over a country that was basically intact and that the imperialists were just benignly looking on. No, things were in this state of near ruin and the imperialists and reactionaries were coming at them. The world’s first oil embargo was applied to the new Soviet state.

But state power was held on to... and fragile as it was, the Soviet Union was still a beachhead in the fight for a new world. This had everything to do with Lenin’s leadership and the existence of a vanguard party.

Radical Changes: Women

Question: But there’s a line of attack that holds that the emergencies and threats became an excuse for the Bolsheviks just to betray people’s hopes.

RL: Look, this was a revolution fighting for its life, but it was a state power fighting to carry forward a social revolution. Take the oppression of women.

The revolution moved quickly to take important measures. It abolished the whole church-sanctioned system of marriage that codified male authority over women and children. Divorce was made easy to obtain. This was very important in providing women with greater social freedom. Equal pay for jobs was enacted. Maternity hospital care was provided free; and in 1920 the Soviet Union became the first country in modern Europe to make abortion legal.15 This was way in advance of the capitalist countries of the time, coming when the right to divorce was usually subject to all kinds of religious restrictions if it was even allowed at all, and where women couldn’t even vote in many capitalist countries or had just won that very basic right—and this took place just a few short years after U.S. authorities tortured imprisoned suffragette hunger strikers by force-feeding them.16 Pretty closely connected to this in spirit was the fact that the Soviet Union legalized homosexual relations.

In the mid- and late 1920s, you had something else going on too. You had struggles against patriarchal customs in some of the Central Asian republics. A lot of this was connected with oppressive Islamic... Sharia law. Women were challenging this, and the socialist state gave backing to women (and enlightened men) involved in these struggles... and was actually encouraging these struggles.

The government provided funds for local organizations of women. A big focus of struggle was the practice of arranged marriages that still persisted in different areas, and also bridal price... the payments made between the marrying families. For a while, communists from the cities went to these areas to aid the campaigns. And this got very intense at times, with backward forces attacking organizers. And local women activists came forward. In 1927, a major offensive was launched against the centuries-long practice of the forced veiling of women—an oppressive signifier, then and today in the world, of patriarchal control over the faces, bodies, and humanity of women.17

In Soviet newspapers and schools, there was lively debate about sex roles, marriage, and family. Science fiction works envisioned new social relations. And, frankly, when you compare what was going on in the Soviet Union with the state of patriarchy, enforced patriarchy, in the rest of the world then and now... this does sound like science fiction!

Never before had a society set out to overcome the oppression of women... never before had gender equality become such a societal focus. People need to know about this. People need to learn from this. We need to learn from the strengths of this, which were by far principal, especially in this period, and we also need to learn from some of the weaknesses in their understanding, which I’ll address a little later.

Radical Changes: Minority Nationalities

Question: You mentioned minority nationalities. How was discrimination being taken on? Obviously, here we are in the U.S., and racism is alive and well. But there’s a question among progressive and radical activists about whether socialism, communism, can really tackle racial and national oppression.

RL: The Bolshevik revolution created the world’s first multinational state based on equality of nationalities.

The new socialist state recognized the right of self-determination—that is, the right for an oppressed nation to separate itself from an empire or from a dominant nation and gain independence. Finland, for instance, which had been held in a subordinate position in the Russian Empire, became independent. The 1924 Soviet constitution gave formal shape to a multinational union of republics and autonomous regions. That’s why you have this Soviet union... the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which included 12 large national republics and 25 autonomous regions (and many smaller districts and other units). The new central government recognized the right to autonomy—this meant self-government, in republics and regions.

In a 1917 decree, all minority nationalities were granted the right to instruction in native languages in all schools and universities.18 There were incredibly exciting things that were happening in the 1920s and early 1930s. Many minority nationalities that had no written languages were supplied with scripts. The Soviet state devoted considerable resources to the mass production of books, journals, and newspapers in the minority regions, and the distribution of film and encouragement of folk ensembles.

Books were being published in over 40 non-Russian languages. Let’s stop right here. What’s going on in the U.S. right now? You see “English only” campaigns in parts of the country! Compare that to the Soviet Union. In the 1920s, Russians were being encouraged to learn non-Russian languages—and great-Russian chauvinism, similar to white-American privilege and dominance, was publicly and strongly rebuked as a poisonous influence in society.

The nationalities policy called for “indigenous leadership” in the new national territories. The idea was to bring forward leaders from the populations of these areas. And all kinds of efforts went into training Party leaders, government, school, and enterprise administrators from among the former oppressed nationalities.19

The persecution of the Jewish people—who, by the way, had been overwhelmingly confined to a specific area called “the Pale” under the rule of the Tsar and had been periodically subjected to lynch-mob-like “pogroms”—was ended. After the victory of the revolution, the new state officially outlawed anti-Semitism. Jews entered into professions from which they had long been banned, and occupied important positions of authority in the state administration. Theater companies performing in Yiddish were formed. During the Civil War, the Bolshevik leadership fought against the influence of anti-Jewish ideas among sections of the peasants and others.20

This spirit of combating national oppression and the active encouragement of ethnic diversity permeated the early Soviet Union. It was one of the defining features of the new society and state.

Where else in the world were things like this happening at the time? A one-word answer: nowhere. But we do know, or at least people should know, what the situation was in the United States. Segregation was the law of the land. Jim Crow was in full effect. The Ku Klux Klan marched down the streets of Washington, D.C. in full regalia during this time, and the rule of the lynch mob terrorized African-American people in the southern U.S. And in the “enlightened North,” white mobs would run amok through northern cities, killing 23 Black people in Chicago alone in one 7-day rampage in 1919, one of 25 similar outrages in that summer alone—the very year that the “Reds” were fighting a civil war to create a new world in what would be the Soviet Union.21

When Paul Robeson, the great African-American actor, singer, and radical, first visited the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, he was deeply impressed by the revolution’s efforts to overcome racial and national prejudice and deeply moved personally by the way he was treated both by officials and ordinary people in the new socialist society. Ethnic minorities weren’t being lynched in the Soviet Union like Black people were right then in the U.S. South.22 The new Soviet Union wasn’t a place where racist films like Birth of a Nation, which extolled the KKK, and Gone with the Wind, which glamorized white plantation culture, were being produced and upheld, and still are, as cinematic icons. The new culture in the Soviet Union was promoting equality among nationalities, and celebrating the heroism of people fighting oppression.

The U.S. and the Soviet Union were two different worlds.

The Arts

Question: You’ve mainly focused on economic and political changes. But what happened in the realm of the arts?

RL: Well, first off, the things I just talked about were definitely political—but they also took in the ways in which people related to each other in social life, and how they even thought about the world, and themselves. And this also got reflected in the arts. From the time the revolution came to power in 1917 through the 1920s and early 1930s, there was tremendous artistic vitality in the Soviet Union. There was a lot of debate about the role and purpose and character of revolutionary art in contributing to building a new society and world.

You had world-class innovation in the arts. I mean leading avant-garde visual artists like Rodchenko and Malevich, filmmakers like Eisenstein and Dovzhenko23... were creating very exciting work fired by a radical re-imagining of the world, by a desire to radically remake the world... and doing that through all kinds of new and unprecedented techniques, like montage in film.

You know, I heard the curator of a recent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art dealing with the early 20th century movement of abstract art. She was interviewed on TV and was asked about where at the time this art was actually influencing society. And she quipped: You know, the only place in the world where the avant-garde ever held state power... was the Soviet Union. She was being whimsical but making a real point.

Artists in the Soviet Union were doing incredible and pathbreaking work as part of a bold transformation of society and consciousness. One famous architect designed structures to convey internationalism; other architects and urban planners were rethinking the grid of cities and housing, to foster community and cooperation... even involving things like the redesign of household furniture.

All kinds of views and debates were reaching the public... issues of the importance and role of art, or the relation between artistic experimentation and new social relations. There were all kinds of groupings and associations of artists and cultural workers, journals, manifestos and proclamations.

And world-class artistic innovation and theoretical exploration became joined to mass needs and, if you want to use the term, “everyday acts.” Especially in the visual arts, where you had these great breakthroughs in poster art, in lithography, that aided the battle against peasant illiteracy.

There were mass campaigns to overcome illiteracy, and very quickly the Soviet population achieved high levels of literacy.

You had public health campaigns—I mean basic things like encouraging people in the countryside to practice essential hygiene—where visual artists were called on to help find ways to get the messages across. They festooned trains with bold graphics.

You had lots of open-air theater, theater to the masses. You had artists taking part in street festivals and pageants... these were very popular forms of mass cultural expression. Poets and satirists had mass followings.24

My point is that the Soviet Union was an exciting, a great place to be, in the 1920s and early 1930s. Unlike anything else on the planet.

Joseph Stalin

Question: You never really hear about those things. What was Stalin’s role in all that? And maybe you could speak to what his role was overall, too. The conventional wisdom is that he was some kind of lunatic or tyrant.

RL: There’s a lot here. There is, and here I use the phrase of the historian Arno Mayer, there is this “ritualized demonization” of Stalin.25 And let me say straight up... people who just accept this “ritualized demonization” and repeat it... are victims of “brainwashing.”

We have to set the record straight and we have to look at individuals and events in a scientific way, getting at the real context: what was happening in society and the world; how they understood what they were facing; and, on that basis, what were their goals and objectives. In short, we have to demystify.

Stalin was a genuine revolutionary. The kinds of radical social changes taking place in Soviet society that I have been describing... all this was very much bound up with Stalin’s leadership. Lenin died in 1924. Joseph Stalin assumed leadership of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union. Now the question had been posed in the mid-1920s. Could you build socialism in the Soviet Union? Could you do this in a society that was economically and culturally backward?

Marx had expected that socialist revolutions would break out first in the more advanced capitalist countries—because there you had a large industrial working class and modern industrial economy that could be the basis for a developed socialist economy and society. But that’s not how history developed.

Lenin said, Okay, we don’t have what was theoretically expected to be the developed base for socialism... these are the cards we’ve been dealt, we have to build socialism and create a better foundation... and we have to promote the world revolution. And the Soviet Union played the initiating role in forming an association of communist parties... this was the Third Communist International.

But the challenges actually mounted and intensified. A decade into the revolution, 1927, and the Soviet Union still stood alone, as the world’s only proletarian state... and there was no certainty that revolutions would take place in other countries. So, again, could you hold out, and carry out socialist economic and social transformation?

Stalin stepped forward and fought for the view that the Soviet Union could and must take the socialist road in these circumstances. If you didn’t do this, the Soviet Union, the world’s first socialist state, would not be able to survive. It would not be able to aid revolution elsewhere. Anything less would squander the sacrifices of millions in the Soviet Union, and betray the hopes of oppressed humanity worldwide. This was the orientation that Stalin was fighting for... and Stalin led complex and acute struggles to socialize the ownership of industry and to collectivize agriculture.

Constructing a Socialist Economy

Question: Are you referring to the debate over building “socialism in one country”?

RL: Yeah. At the time, this was in the late 1920s, Stalin saw socialist construction in the Soviet Union as part of and contributing to the advance of the world revolution. And he and others in top leadership were expecting a new tide of revolution, especially from Germany. Their thinking was that the Soviet Union could help spark that new wave... although there was still going to be necessity to “go it alone” for a while.

Question: Could you briefly describe the economic situation in the Soviet Union in the mid-1920s?

RL: Agriculture was still backward, and couldn’t reliably feed the population. Industry was limited and could not furnish the factories and machines needed to modernize the economy. Russia had been a society where intellectuals were a tiny segment of the population, where only a narrow slice of the population had higher technical and liberal arts education. And, always, there was the looming threat of imperialist attack.

These were the real economic and social contradictions faced by real human beings trying to remake society and the world.

The Soviet state under Stalin’s leadership moved to create a new kind of economy. For the first time in modern history, social production was being carried out consciously according to a plan designed to meet the needs of the people and shaped by overall social aims and goals to end oppression and poverty and change the world... a plan that was coordinated as a whole. This was an amazing breakthrough. Production no longer hinged on what could make a profit for a capitalist.

I’ve talked about the “long dark night” being broken. Here in this one piece of liberated territory in the world, surrounded by hostile imperialist and reactionary powers, something utterly radical was being undertaken. Instead of being exploited by a minority, dominated by a minority of owners... instead of the social product of people’s labor and energy serving the maintenance of the division of society into classes... now there was an economy serving the needs of society and revolutionary change.

Question: But the way this is portrayed is that there was this top-down master plan imposed on society.

RL: The First Five-Year Plan in the Soviet Union was launched in 1928. The slogan of the First Five-Year Plan was “we are building a new world.” Millions of workers and peasants were fired with this spirit. In factories and villages, people discussed the plan: the difference it would make for their lives—and for the people of the world—that such an economy was being built. At factory conferences, people talked about how to reorganize the production process. People volunteered to help build railroads in wilderness areas. They voluntarily worked long shifts. At steel mills, they sang revolutionary songs on the way to work.26

Never before in history had there been such a mobilization of people to consciously achieve planned economic and social aims.

And let’s ask again: what was happening in the rest of the world? The world capitalist economy was languishing in the Depression of the early 1930s—with levels of unemployment reaching 20 and 50 percent. People were starving in major cities like New York and Berlin, and if you’ve ever seen the movie The Grapes of Wrath you get a picture of what small farmers in the U.S. faced... the richest country in the world.

Back to the Soviet Union, there was also the transformation of agriculture, collectivization...

Struggle in the Countryside

Question: That’s one of the things that people raise to me as a negative thing.

RL: Well, they’re dead wrong. Collectivization spoke to real needs and contradictions in society... and the world situation the Soviets were facing.

We have to go back to the Civil War that I was talking about. It had caused tremendous destruction and dislocation to the economy and society. Conditions were desperate. People in the towns and cities were hungry, industry was barely functioning, and peasants were reluctant to grow crops because during the war the government had been channeling large amounts of agricultural produce to feed the army and the population.

It was necessary to restore and stimulate economic production and to rebuild transport and communications. The revolutionary leadership took certain measures, known as the New Economic Policy or NEP. These included the reintroduction of some private markets and various forms of capitalist ownership and activity—although the socialist state kept control of large-scale industry and banking. And foreign investors were allowed in. These measures were seen by Lenin and the revolutionary leadership as a temporary retreat in order to revive the economy. The NEP did that, but over time, it also gave rise to new problems.

There were food shortages in the cities, especially with the urban population growing. Land had been redistributed to peasants after the seizure of power in 1917. But through the 1920s, a section of rich peasants were gaining strength in the rural economy that was still a private-based economy of small landholders. The rich peasants, or kulaks, as they were called, had large land holdings, and were consolidating greater ownership. And the NEP had given rise to forces (the popular expression was “NEP men”) who dominated the milling and marketing of grain and finance in the countryside. Social polarization between the kulaks and the poor peasantry was increasing.27

Stalin and others in leadership felt they had to move quickly to create large units of agriculture in the countryside. This would raise productivity and surround the kulaks. It would also accelerate the “proletarianization” of the peasants, bringing more people into the cities and industry, and lessening tensions between the new society and peasants who were still wedded to private ownership.

Collectivization was a huge social movement that drew in, activated and relied on the poorest farmers as its base, and worked to involve as many people as possible. Dedicated worker-volunteers from the cities went into rural areas to forge collectives. Artists, writers, and filmmakers went to the front lines to tell the stories of what was going on. Traveling libraries were sent to teams in the agricultural fields. In some regions, farms had their own drama circles. Religion, superstition, and mind-numbing tradition were challenged.

People lifted their heads and became tuned in to what was happening in society overall. They discussed the national plans and national developments. Women, whose lives had been determined by oppressive tradition and patriarchal obligation, became tractor drivers and leaders in the collectives.28

Question: But collectivization did meet a lot of resistance.

RL: Yes. On the one hand, this had to do with the class struggle in the countryside—where you had the kulaks and other traditionally privileged forces digging in and mobilizing resistance to the changes and social forces that I’ve been talking about. That was the main thing.

On the other hand, some of this resistance was connected to mistakes that were made. Mao wrote about this in the 1950s. While recognizing the tremendous and unprecedented character of collectivization in the Soviet Union, at the same time he also had serious criticisms of how Stalin approached it. It took place before the peasants themselves had gained experience cooperating with each other, working the fields and using tools cooperatively. There wasn’t sufficient political and ideological work done, to create the understanding and atmosphere enabling peasants to act more consciously to achieve collective social ownership. And the state took too much grain from the countryside—this put unnecessary pressure on peasants and led to resentment.29

Changing Circumstances and Changing Thinking

Question: Wait a minute—what do you mean by “ideological work”?

RL: I mean work to change not just what people do, but to win them over to think in new ways and to unleash their initiative on that basis to transform the world. The lives of small farmers—each person owning their own land, surviving or not by dint of their own efforts, in opposition to others who compete with them—pit them against each other, and this shapes their thinking. Stalin tended to think that if you mechanized agriculture and made it collective, people’s thinking would sort of be naturally transformed; but the whole process is way more complex than that, and you actually have to work on transforming not just what people think, but how people think, well before the revolution, AND through each phase. As I said, this was a point of Mao’s and it’s something that Bob Avakian—BA—has both built on and taken to a new level in the new synthesis of communism.

So to return to Stalin. He was trying to solve real problems in society, like how to move forward and out of private agriculture at a time when the Soviet Union was facing international encirclement. But, as I mentioned, the approach was a bit mechanical; he was seeing the creation of higher levels of ownership and bigger farms with more advanced technology as the crux of the matter... and downplaying the whole ideological dimension and not grasping that people’s values and thinking have to change, and their relations with each other in production and society have to change, and leadership has to be working on this.30

The same problem existed in the approach to industrial planning—a mechanical view that by building up socialist heavy industry, you would be securing the material foundations for socialism. But as Mao said, this was years later, “What good is state ownership of factories, warehouses, if cooperative values are not being forged?” And socialist economic development has to be oriented to breaking down gaps between industry and agriculture, between mental and manual labor, between worker and peasant. Stalin paid some attention to overcoming these contradictions, but it was seen as a secondary task in relation to creating a more modern industrial-agricultural foundation.31

A Turning Point: The Revolution Is Crushed in Germany and the Nazis Come to Power

Question: As I understand it, there was a clear turn towards more, if you want to use the word, conservative policies overall in Soviet society from the mid-1930s onward. Is that right? And if so, why?

RL: The Soviet leadership and masses did not get to choose the circumstances in which to make, defend, and advance the revolution. And by the mid-1930s, the revolution was under heavy assault and facing a very unfavorable and perilous world situation. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria on the Soviet Union’s eastern borders. In 1933, the Nazi party, led by Hitler, consolidated power in Germany.

As I said, the Soviet leadership had been expecting a revolution to take place in Germany. But the Nazi regime effectively crushed the German Communist Party and began to embark on a program of militarization. At the same time, pro-fascist forces had gained strength in Hungary, Bulgaria, and Romania, and the Baltic countries, including Poland. In Spain, the Western powers stood idly, as General Franco led an uprising against the Spanish Republic, actively aided by Hitler and Mussolini. Germany and Japan had signed an Anti-Soviet Pact.

The growing danger of inter-imperialist war and the likelihood of a massive imperialist assault on the Soviet Union was profoundly shaping economic and social policy in the Soviet Union.

Question: So what were the implications of that?

RL: War was looming. And, as with all of the challenges facing the Soviet revolution, there was no prior historical experience for dealing with the magnitude of a situation like this... the likelihood of a full-press onslaught by German imperialism against the Soviet Union. Stalin and the Soviet leadership approached this in a certain way. The assessment was that there had been this big leap in socialist state ownership and the development of the productive forces. And it was time to hunker down and prepare for the eventuality of war.

There was a push for greater discipline and stepped-up production in the factories to have a war-fighting capacity. There was great emphasis on administrative measures, material incentives (paying people more to work harder), and on management technique and technology.

The radical social and cultural experimentation of the 1920s and early 1930s was reined in. It was seen as being too removed from urgent production and political tasks and too alienating of the broader ranks of workers and the newer educated technical strata that were rallying around the regime.

There was a premium put on unity in the face of the growing war threat... and unity was being forged around a kind of national patriotism.

Internationally the Soviet Union was calling for and attempting to build a global united front against the fascist imperialist powers. It subordinated, and even sacrificed, revolutionary struggles in various parts of the world to the goal of defending the Soviet Union. The Soviet leadership saw the defense of the Soviet Union as being one and the same as the interests of the world revolution.

All this was very problematic. It went against, and stood in contradiction to, what the revolution was about and to its overall main character. The revolution was facing the need to prepare for attack and war that could destroy the whole revolution. This was real and monumental. But Stalin’s approach was seriously flawed.

Mistakes and Reversals

Question: Could you elaborate on that a little—like, how did they justify this turnaround?

RL: Well, I talked about Stalin’s tendency to see things mechanically and statically—that is, to not see how there are contradictions within societies, processes, individuals—really, everything—that may not be on the surface, but that are actually driving forward change within that thing. You know, like you look at an egg and just by going by the surface you wouldn’t know that there was this potential chicken inside, growing and growing and eventually going to burst out of that egg and become a whole different thing.

This kind of mechanical or static thinking crept into and began to increasingly color his view of socialism... that there was this socialist state that had to be defended at all costs against the onslaught he could see coming, and a lot of things got justified in the name of doing that defense which were actually undercutting the socialist character of the state.

For example, Stalin began to make concessions to parts of the population that were still very religious and traditional in their thinking, or were strongly influenced by Russian nationalism, or both. Now, yes, you were 15 years into the new society—but one thing that we have learned is that there are huge sections of the people that don’t give up all that old thinking overnight. So this presents challenges in terms of waging ideological struggle, carrying on educational work, and promoting a scientific world outlook in society, while upholding the right to religious worship. But, as Stalin saw it, you had to make concessions to that kind of thinking and those kinds of forces like the Russian Orthodox Church in order, as Stalin saw it, to strengthen unity for the war effort.

The government also began to go back on some of the earlier advances around women and gay people, for instance. Some of the tremendous, and at that point in the world unique, advances I talked about earlier—including the right to abortion—got reversed. And the rights for gay people were also reversed. And more generally the traditional family was being extolled and traditional relations were being reinforced. This was both a very serious error and also betrayed a certain lack of depth to understanding the importance of gender relations in the overall transformation of society. And this kind of thing was based again on the assumption that the socialist character of the society was more or less assured and the main thing you had to do was to defend it.

Now I don’t want to minimize in any way the scale of the threat the Soviet Union faced. Stalin and those around him were the first people to lead a socialist state, they had this tremendous responsibility to defend it, and here was the most powerful army in the world sitting next door with the leader of that army making very clear that he intended to destroy that socialist country. And let’s remember that the Nazis very nearly made good on that threat, and killed some 26 million—yes, 26 million!—Soviet people in the course of trying to do that.

I’m not saying this to justify these errors in the least. I’m saying this so that we really grasp what they faced and how in the face of that kind of huge pressure we must and we can do better in the future. And without getting into all that now, this underscores the importance of the work done by Bob Avakian in grappling with this whole experience and the way that he has approached this, and through that process developing the new synthesis of communism.

Question: What about the gulags32 and executions? When you say Stalin, this is probably the first thing people start talking about.

RL: The international situation I just described—where the very existence of the Soviet Union was in the cross-hairs—also set the context for the purges and repression of the late 1930s.

And look, when we talk about literally grievous errors, some of what went on during the period of 1936–1938 is part of what we mean. Many innocent people suffered repression: economic officials, military officers, Party members who had been in opposition in earlier years and others who were seen as potential sources of opposition, including people from the intelligentsia. People’s basic legal rights were violated and people were executed on the basis of those violations. So this was, as I said, grievous.33

Now there are two contending ways of understanding what was going on—and only one of them gets you to the truth. You can declare that Stalin was a monster, a paranoid despot who just wanted to accrue “absolute power”... end of discussion. That’s the line of attack of anti-communist historians and cold-war propagandists.

Or, you can bring a scientific approach to this moment in the history of communist revolution, to understand what happened and why. You look at what Stalin and the leadership were actually facing at that point in terms of the virtual certainty of massive attack, you look at the fact that there were indeed some counter-revolutionary groups and some elements in the Party and army who seem to have been intriguing with one or another imperialist power in the face of that, you analyze the framework they were using to understand all that, and then you evaluate what was done politically in the face of that. And if there were errors—and as I said, there were, some of them very serious—then you strive to understand what it was in their understanding and approach to those problems that gave rise to these errors.

A Matter of Orientation

So I want to get into what led to those errors. But before I do, there’s something else to bring to this discussion... as a matter of basic orientation. Even acknowledging the serious excesses that took place, still, what happened in the Soviet Union does not hold a candle to what happened as a result of one single event in U.S. history: Thomas Jefferson’s decision to make the Louisiana Purchase, which played a key role in expanding and prolonging slavery in the U.S.

One hundred thousand slaves, a third of them children, would be sold in the markets of New Orleans before the Civil War.34 Slaves picked cotton from before dawn to after dark. They cleared disease-infested swamps. They were worked as if they were beasts of burden. Jefferson’s slave-owning peers carried out pervasive and massive rape, barbaric punishments, and even the selling of children away from their parents. Slave owners on the Eastern seaboard, including Jefferson himself, profited greatly by the expansion of slave territory. And in the newly acquired territory, the genocide against the Indian peoples gained terrible new impetus.

Thomas Jefferson acted consciously and methodically to expand and consolidate the system of chattel slavery, literally. He created a living hell that would last for nearly six decades, all in the pursuit of empire and profit.35

Or you look at the massive amount of killings carried out by the U.S. over the past decades at a time when nobody could argue that they were facing any kind of serious threat to their very existence—and we’re talking several million killed in Korea, several million more killed in Indochina, the hundreds of thousands killed and millions displaced in Iraq, all of those as a result of direct U.S. military intervention—and that’s not even touching on the many murderous proxy wars they have sponsored in Latin America and Africa—and again, for what? For the maintenance of a worldwide system of exploitation and misery.

Stalin, on the other hand, made errors, even serious errors, in a situation in which the Soviet Union was in desperate circumstances and facing dire threats. But he made those errors in the context of defending a world-shaking revolution aimed at ridding the world of slavery in its modern form.36

People have to judge any historical figure, or any historical event, in the whole context of what was taking place, what vital interests were in play and at stake, and what were the aims and objectives of the person or group in question—in order to determine the essence of the matter. At the same time, as I said, we need to evaluate Stalin’s and much of the Soviet leadership’s understanding of the tensions and contradictions in society, and their approach to dealing with this. And there were serious problems.

Two Different Kinds of Contradictions

Question: What do you mean by that? Problems in how he was understanding things? Does this tie in with what you said earlier about a static view of socialism?

RL: Yes. Earlier I mentioned that by the mid-1930s, socialist and collective ownership had been achieved in the main sectors of the economy. The old propertied classes had been overthrown and private capitalism had been pretty much transformed.

Stalin analyzed that there was no longer an economic basis for exploitation... and therefore there were no longer antagonistic classes in socialist society. The understanding was that there were two non-antagonistic classes: the workers and the collectivized peasants, and then a stratum of new and old intelligentsia and white-collar professionals. The old ruling class had been overthrown by the revolution and civil war. As Stalin saw it, there were remnants of the old order—but, as I said, no antagonistic classes... no bourgeois forces internal to society. And these remnants of the old order... again I’m characterizing the understanding... they could only be propped up externally.

So the threat to Soviet society was seen as coming from agents of the deposed classes, cultivated and supported by foreign capital. And you had this whole discourse of foreign spies and wreckers, of plots and conspiracies from outside. There was real subversion, but Stalin tended to view all opposition in society as coming, in some way, from the outside. And the struggle against counter-revolution was seen as a kind of counter-espionage operation. It was this mindset that led to the serious mistakes I described earlier.

But Stalin’s analysis was wrong. In fact, society was teeming with class differences and contradictions. And not all coming from the outside... though, as I’ve been pointing out there was the threat of intervention and war and what’s going on in the world profoundly shapes the struggles in socialist society. All this was discovered by Mao, and on that basis he was able to lead the Chinese Revolution in a profoundly different way of handling these contradictions, and the different kinds of struggle they give rise to.37 And I’ll get into that, later in the interview.

Stalin was mixing up these two types of contradictions. You had people in Soviet society in the 1930s who were raising objections to different policies of the socialist state... really who were dissenting. But Stalin was treating all these differences as antagonistic ones, and he linked all this to external threats... to external subversion. Repression should only have been directed against enemies. But it was used against people who were expressing disagreements and against people who were making mistakes in certain responsible positions. As I said, Mao grasped the problem here and got deeper to the truth of the dynamics of socialist society. And Bob Avakian has built on this pathbreaking insight of Mao, and the experience of socialist society more broadly, and developed a deeper scientific understanding of socialist society and a more expansive vision of the importance of dissent and struggle between contending ideas in that society.

But Stalin didn’t have this understanding. And he was relying on purges and police actions to solve problems—rather than, and this was what happened during the Cultural Revolution in China... rather than mobilizing the masses to take up the burning political and ideological questions on the overall direction of society and opening things up. Instead there was this whole approach of hunkering down to defend the socialist state.

And you had this serious departure from internationalism... the Soviet Union backing away from the socialist state’s responsibility to promote the world revolution. There was this view that nothing was more important than protecting the socialist state and that nearly anything was justified in doing this—including entering into a sort of realpolitik, or political intrigue—with the imperialists. Now just to be clear, there is a role for diplomatic relations that socialist states undertake with imperialists—you can’t exist in a constant state of war, for one thing, you’re going to need to trade, and so on—but these have to be on the basis of principle... on the idea that those relations are subordinated to the advance of the revolution. But too often, in navigating that period, this got lost.38

A Crucial Relationship: Advancing the World Revolution, Defending the Socialist State

Question: But you’ve been emphasizing the real need to defend the Soviet Union, and how this was impacting the decisions Stalin was making.

RL: Yes, but there was not a correct scientific understanding of this. You see, Bob Avakian identified—and no communist leader and theorist before him even conceptualized things in these terms—that there is this real contradiction between defending the socialist state and advancing the world revolution and at times this can be very sharply posed. This is a key element of the new synthesis of communism, in the further development of the science of communism.

You don’t let the imperialists just destroy the new socialist society. It has to be defended. But that can come into contradiction with supporting revolution in other parts of the world... in terms of where you are putting resources, how you are carrying out diplomacy, and how you are organizing socialist society, and preparing people ideologically in terms of sacrificing for the whole world revolution. So you are going to have to recognize that contradiction and learn how to handle it.

Stalin, and even Mao, later, when he led the revolution in China, tended to equate defending the socialist state with acting in the interests of the advance of the world revolution. And again, in evaluating this, you have to remember that this was the first time anyone had ever faced this situation and there was no previous experience to go on, you have to remember the real and existential threat they faced, and you have to remember that both of these leaders never caved in to imperialism and that Mao, in particular, fought for revolution and made advances in the revolution up until his very death. But this objectively amounted to putting the defense of the socialist state above advancing the world revolution.

It’s not that Stalin and Mao consciously set out to subordinate the world revolution to the defense of the socialist country. Rather, because they understood this extremely complex and sharp contradiction in a certain linear way—revolution would be won in this country, then in that country... and the world revolution would proceed through a process of defending and adding on new socialist countries—because of that understanding, they made errors in policy.

On the basis of digging deeply into this, Bob Avakian has brought forward new, scientific understanding: the principal role of the socialist state is to be a base area for the advance of the world revolution. It has to defend itself on that basis and be prepared to put its survival on the line in periods when the world revolution can make great advances. And it has to handle the real and very difficult contradictions involved correctly in all of this.39

So these are some important lessons from what was going on in the Soviet Union in the 1930s.

Question: And of course, then the Soviet Union was invaded by German imperialism in 1941.

RL: You know, the history of the Soviet Union, when it was socialist, was a history of a society waging war, preparing for war, or dressing the wounds of war. In June 1941, the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. They threw the most modern army in the world and most of their military might against the Soviets. Hitler made it clear to his troops that he expected them to discard every principle of humanity in what was to be a war of total annihilation.40

The Soviets fought with incredible heroism. Twenty-six million Soviet citizens lost their lives in World War 2, more than 1 of 8 in the population.

But you have this contradiction. The Soviet Union came out of World War 2 militarily victorious. But the revolution was weakened politically and ideologically. By that I mean that the errors I described above had corroded and undercut people’s understanding of the goals of communist revolution and had actually reinforced weaknesses in the way people were attempting to understand the world, and how to transform it. People were still fighting to build socialism and refusing to cave in to imperialism, and this definitely was being led by Stalin. But they also had become muddled in their understanding of the difference between nationalism and internationalism... between revolution and reform... and about what really constituted a scientific approach to nature and society.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, new bourgeois forces within the Communist Party maneuvered to seize power; and in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev, a high official in the party and government, took over the reins, consolidated the rule of a new capitalist class, and led in systematically restructuring the Soviet Union into a state-capitalist society.41 This was the end of the first proletarian state.

Question: So how do you put this in perspective?

RL: The Soviet revolution was about the slaves rising up with vanguard communist leadership—and forging a whole new way to organize and run society, a whole new way to relate to the world... not to plunder and conquer it but to contribute to the emancipation of humanity. Its defeat was a bitter setback, made more so by the fact that people did not have the scientific tools at the time to understand the character and source of that defeat.

Despite the errors I’ve described, the revolution of 1917–56 represented the first steps, apart from the short-lived Paris Commune, along the road of emancipation, towards a world free of oppression and exploitation. It inspired people throughout the world. But that road has to be forged... the understanding of what it’s going to take has to be deepened and extended. It doesn’t come automatically or spontaneously. There’s a “learning curve,” if you will.

But to learn and learn deeply requires a scientific understanding of society and how to transform it. It requires the further development of that science... I’m talking about the science of communism. It’s a question of identifying and analyzing the problems and challenges in the process of getting to a classless world... and forging solutions, and developing new insights into how to understand what you are facing.

This is what Mao Zedong, the leader of the Chinese revolution, did... he took the project of emancipation, the communist revolution, to a whole new place of understanding and practice. This was a new breakthrough for humanity, more radical and more emancipating. And that’s what we’ll get into next.

Chapter 4: China—One Quarter of Humanity Scaling New Heights of Emancipation