A Conversation with Carl Dix:

Why People Have To See 12 Years a Slave

February 17, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

There were many important and significant films in 2013, both fiction and documentaries. Fiction films like Fruitvale Station, The Company You Keep, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Dallas Buyers Club, Don Jon, Lovelace, Mother of George, and others were both artistically well done and shed important light on different dimensions of life. Documentaries like Dirty Wars, The Act of Killing, The Central Park Five, and others exposed, sometimes in vivid and powerful ways, parts of reality that are normally suppressed.

At the same time, one film deserves particular mention: 12 Years a Slave. This film tells the story of Solomon Northup, a free Black man living in New York State in the 1840s—a time when slavery remained at the heart of the U.S. economy. Northup was kidnapped and enslaved, ripped from his family and forced to endure 12 years in the network of concentration camps that was life for African-American people in the U.S. South. The director makes you look at life for the slaves and the whole network of social relations involved in slavery; it is unflinching, austere, and magnetic. The cast portrayals are powerful, with Chiwetel Ejiofor and Lupita Nyong'o in particular bringing to life unforgettable characters; you feel their characters as if from the inside.

Revolution urges our readers who have not seen this movie to see it; and if you have seen it, see it again while it's still in the theaters and on the big screen, and then discuss it. Now's the time!

In that spirit, Revolution got together with Carl Dix to talk about this film. What follows is an edited transcript of some of the remarks from the interview/discussion that was conducted. (If you have not yet seen the film, you should know that the interview reveals many plot points.)

***

On the overall significance of the film...

Revolution: Could you talk a bit about the significance of this film, being out there broadly in society, and up for major awards?

Carl Dix: It's very important and very fine that millions of people are seeing this story about slavery, seeing this story about the history of this country, the real history of this country, and a movie that is very well done, is based in the reality of slavery with a cast... and basically people behind the picture who really felt like this story needed to get out. I mean everybody from the director to the screenwriter to the people in it felt like we need to have this story out and watched by millions of people in this country. And then the way that they did it and brought to life the brutality, the dehumanization that characterized slavery I thought was—it was just astounding. Here's a free man getting kidnapped into slavery, waking up in chains and then finding himself with others, some of whom are in a similar situation, and others of whom were enslaved already and were being sold down the river, down to Louisiana where it's kind of like there is no way out of this. And then there's the things that he's going through, and then there's the things that all of the people who are enslaved are going through—like the ripping apart of the family right at the beginning and the cavalier way in which it's done and related to by the people involved in the slave trade on different ends from that initial buyer, and the seller. The woman lands at the plantation and is sobbing about her kids and the mistress says, "You'll get over it. It'll go away in a short while." Like it doesn't really matter to you, you're not really human so it won't bother you that long that your kids were ripped away from you and you have no idea where they ended up and what fate awaits them.

From 12 Years a Slave: Solomon Northup (left) and other slaves awaiting being auctioned off at the Slave Market in New Orleans. Photo: Fox Searchlight Pictures

And then even some of the things that might in one sense seem smaller but actually have their own significance... like when the family was being ripped apart actually the guy who was buying the mother was trying to persuade him to cut him a deal and he'd take the kids. And the guy was kind of like... I forget the exact term he used, but his humanity extended to the edge of a coin. In other words, "oh yeah, I've got humanity but that's trumped by the fact that this is property and I'm out to get the best return on that property and if you can't match it then, yes, I will take these children, I will send them to who the hell knows where because that's what this is about. That's what this is based on and it trumps any other considerations." And then the way that people were forced not only to endure brutality, but even if it wasn't like you were directly experiencing it you did experience it because you had to watch as this stuff goes down, you had to live your life and know that there is nothing you could do about it. And this comes out in several scenes: the scene where Solomon is forced to whip Patsey and he doesn't want to do it but then it's like we'll both get whipped if I don't and she's saying I'd prefer you to do it to him doing it, so then he does it but he's kind of not really unleashing it and then it's like "I'll kill you and every other Black person, every other person I own, every other slave of mine, if you don't do it." So it's like you've got no choice. And then other people have to watch that.

The viewpoint of the film

Solomon Northup (center) in early scene of 12 Years a Slave Photo: Fox Searchlight Pictures

Revolution: Could we go back for a little to the beginning of the film? From the very beginning he's a slave and you see what's going on. And then they pull back to how he got there. There's been a lot of movies where slaves are kind of in it or part of it, or it's even about slavery but the main characters were not the slaves actually. The main characters were other people and then this question of slavery came up. This one was his story and you start out by being where he is as a slave.

CD: Yeah, that is actually very important because I guess there's an argument in the film industry that you can't do that. You can't center a film on the experience of those who are enslaved. Or in other situations, too, the same thing is brought up: well, we can't center it on the experience of those being oppressed and brutalized, we have to figure another way to do the story and come at it from the eyes of maybe someone sympathetic to that. And while there are things that can be accomplished in that framework—it's not like it's always bad to do that—in this film you were right there with Solomon. He wakes up in chains and you're feeling that.

It was kind of like... it actually reminded me of a Richard Pryor skit about where Black humor came from. I think it's in his Bicentennial album and he says: "You all know where Black humor started, don't you? It started in the slave ships. There's two guys in there rowing and one of them starts laughing and the other one says: what's funny? And the other guy says: Yesterday I was a king." And it's not the same thing, but it's like yesterday he was a free man playing the fiddle, enjoying life with his family, a respected member of the community, and then he wakes up in chains. And then he starts to protest and they're going to beat into him that this is now your station and whatever you were yesterday, right now you're our property. You maybe used to be Solomon, but you ain't no more, you're no longer Solomon Northup, we're going to give you a name and you have a new station and there is nothing you can do about it.

And then you're there right next to the brutality, and you can't do anything about it. Like in the scene where one of the whites, Tibeats, gets into it with Solomon over Solomon not following his instructions to the letter—he had had it in for him for a while because he felt like "this is a slave who does not know his place, he does not recognize my superiority"—even over the thing about where they are going to take the produce, the wood, by water. And it's like: "Oh you can't do that. And here is this enslaved person challenging my authority—and then even worse, proving me wrong." And that's an affront to slavery—a Black man, property, standing up to a white man—Tibeats is the part owner of Solomon; the other guy, Ford, holds a mortgage on Solomon. So when Solomon refuses to be beaten and fights back, that's a potential killing offense, and he comes with his people to take Solomon's life for this affront, and the only thing that saved Solomon's life at that point was that he was valuable property to Ford.

So they're not allowed to kill him. But he does get strung up and is... it's just torture. Because he basically had to be on his tiptoes to keep from being strangled, hog-tied, and he's left there for what seemed like a prolonged period. I don't know how much was the elapsed time but it seemed like a prolonged period of time. Then everybody else, all the other people who were enslaved, had to go about their life around that. Everyone knew that they couldn't go in and cut him down. I mean, one woman comes and gives him water, and she even does it kind of on the sly, looking out to see if she's being watched because even this, even giving water to a person in that situation, could be seen as an affront.

People being "property"

So this is the deal: whether he lives or dies depends on him being property, and in this case he only lives because one of his owners doesn't want him killed. And it even came down to who had the right to rape enslaved women. In the plantation that Solomon was at, Patsey belonged to the owner. If another white man wanted to rape one of the slave women he would have known... if he was tied to the plantation, he would have known to steer clear of Patsey, but not because maybe Patsey is reluctant, doesn't return your advances so you can't force her. Stay away from Patsey because she belongs to Epps, but everyone else is fair game and can be raped by anyone associated with the plantation. A white man not associated with the plantation... if he's caught forcing himself on enslaved women, then that's a violation. But not a violation of the woman that he forces himself on, it's a violation of the property rights of whatever white man owned her. And this is something... that's just really on display in the movie.

Revolution: One of the things when you're talking about the scene where Solomon is hanging there and everybody's going on about their business—on the one hand it's clear that if they intervene they're going to get in trouble. But it does pose the question, I think for everybody watching it, of how can you stand by and see this going on? That's the example you're forced to look at, but how many times where things like that happened—it's clear that this was a regular occurrence, this was the way things were done, and that people were put in such a situation that they felt they could not and did not—or rarely did they—stand up. And of course the price of standing up against it was often death or extreme punishment. But it poses the question, I thought, when you're watching this, of how can you just stand by when such horrors are going on And what would it take to break that? I don't know, I thought there were some questions there that are posed not just historically, but...

On legitimacy

CD: I think that's real because you look at that scene with today's eyes, and the illegitimacy of the authority that was enforcing that barbarity, that brutality, that barbarity, is real clear. And sometimes today for a lot of people the brutality that is being enforced throughout society isn't as clearly illegitimate. And so many people are standing aside as unspeakable brutality and illegitimate force is being used against people. And we have to... it needs to be transformed from: well, that's just the way it is, or even those are things done for a reason—to, well, wait a minute: why is this happening, why are more than two million people in prison? Why are hundreds of thousands of people in prison for simple drug possession? Why are the people who get sentenced and put away for that disproportionately Black and Latino? These are things that people have to start looking at with eyes as clear as the ones you apply to: it's clearly bad to hang a guy up because he basically responded to the way you were messing with him by saying some truth—which was Solomon's "affront." But a Black person, an enslaved Black person, in fact any Black person actually in the South in that time, had no right to stand up to a white person. Which is even brought out at the end of the movie—that in legal proceedings around the people who kidnapped Solomon, one or two of them got tried in Washington, DC, and Solomon was not allowed to testify against them because he was Black.

Revolution: One important thing about this movie is that people today don't have a real sense, a living sense, of what this meant, what all this wealth and power is actually founded on. And people should really read the book as well as see the movie to get a really living sense of it.

CD: Just one thing on the book—it actually was widely read back in the early 1850s, like 30,000 copies of it. And it contributed to the challenging of the legitimacy of slavery and the creation of a mood among sections of people that found slavery illegitimate and worked to do what they could to oppose it and to stop it, including things like the forming of the Underground Railroad—people who worked to help people who had escaped slavery to get to the North, sometimes get to Canada, to not only escape slavery but stay free from it, and who even fought slave chasers who went after people who had escaped slavery. Because that became, actually, a business—pursuing runaway slaves was an actual business pursuit. People engaged in it, but it also became a point of contention because there would be times when slave catchers would catch someone and claim that they were an escaped slave, and maybe they even were an escaped slave, but then the abolitionists, or at least a section of them, would gather crowds and fight pitched battles to keep them from taking the person back to slavery. And this book in that period contributed to it, but the story has been covered up or put aside... like you say: "That was then, it was very bad, but it's over, Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves, and today we have a Black president so why do you want to keep bringing this up?" And people need to go back to it because, one, they don't understand the reality—they don't understand the reality, and a big part of that reality is the first quote from BAsics, from the talks and writings of Bob Avakian: "There would be no United States as we know it today without slavery. That is a simple and basic truth." It's just extremely true. The foundation for the wealth and power of America rests on the enslavement of African people and the dispossession of the land from the Native inhabitants. So people do need to be brought back to that and brought back to it on the real, not some prettified, covered over version, but just starkly: "You're right there. Deal with this."

The role of religion

I was thinking too that a part of this thing of it being the way things were had to do with ideological justification and religion in particular. And I thought that the movie brought that out well in terms of... you know you had your different slave masters who went to the Good Book to show you that: "Hey, this was ordained, it's right here in the Bible." Including, "As I whip you, it's ordained that I should do this in the Bible, and that if you're being whipped you really brought it on yourself through your disobedience and not just disobedience to me the individual that owns you but to the order that has been ordained by the most high."

Revolution: Yeah, well, there's two scenes like that. The first one is all the slaves are on their Sunday off and they're there sitting there being lectured by the slave owner about why it's right and just not only that they be owned, that that's part of the natural order, but then if they don't heed the master, then, like you said, they get whipped. And it is excruciating, I think, to see that when you see what's put upon them to justify their condition and for them to then accept it.

CD: I mean, it does come down to where did you get that religion in the first place? And it was brought to you, and even enforced on people, by the slave master. And it was clearly in relation to giving ideological justification to the situation that people were being forced into. And people who came with different religions were forced to stop practicing that and take this up. And it does show you the thing of being forced even to take up a world view that has you at the bottom and being subjected to horrific brutality. I mean, even down to when Patsey was struggling with Solomon to kill her, she even got into some Biblical justification for why it wasn't something he shouldn't do. Because he was like: how can you ask me to do such a hellish thing, and she was explaining to him that no damnation will come from it because it was an act of mercy. Even that was being posed in religious terms and it just kind of showed you just how much that had pervaded people's consciousness.

Revolution: I was watching it and thinking about gospel music today, where some of the voices are beautiful but the words that are coming out are all tied in with the same religion that was part of enslaving people back then and with the same outlook we're talking about and the same way that it affects people of: "it's all in God's plan, we're going to get salvation later"—all of that that people are still being entrapped in.

CD: Still caught up in, and it's still standing in the way of getting at the roots of the oppression and acting to uproot that oppression. And it did... it hit pretty hard, both the historical role that religion played but also the continuation of that kind of role today.

Revolution: There is that scene that goes on after the old slave dies, and it's after Solomon has been betrayed by the white guy who's also laboring there—they're all singing the song and Solomon's not singing, he's not singing, he's not singing. And then at a certain point he starts singing. And I was wondering what you thought of what was going on in that scene.

CD: It struck me that in a certain sense in that scene both his alienation at first from the other enslaved people because he still had hopes of, "Maybe if I could figure out a way to connect with the people I knew in my life before I was kidnapped, they could come down and get me out." But then as the song goes on, I had the sense of him stacking up how long it's been, how he had even been betrayed in his attempt to get word to his family and kind of taking up some of what was clearly part of the way that people—even... I'm kind of grasping for the correct word... how you fit into and went along with stuff. And part of it was the "salvation" in the life beyond. So to me it was like that thing of "salvation in another world" that people were united with except Solomon, but then as the song goes on you could see maybe his hopes were waning and it was kind of a concentration of all the years having to put up with this, even having your hopes lifted at one point and then dashed by the betrayal by the guy he had asked to send the letter. And it was like... and he was in Louisiana. Like you said, there was the Underground Railroad, but it did not reach that far. And it isn't like there was any way out for the several million people who were enslaved—I think it was about four million at that point in the 1850s. So that's what I saw going on in that scene. And like I said, I knew from having known enough about the story that he was going to end up getting out, but at that point in that scene I got the sense of a man who didn't see the way out for himself and was adapting to the way that things were.

Getting out—and controversy over the film

Revolution: What did you think about Bass, the guy from Canada who does finally help Solomon escape?

CD: He was from Canada, so he wasn't indoctrinated in the same way that most white people were in the United States in terms of how they should fit into the whole structure. Because there was a whole structure to force you to go along with the rules—even if you were white there was a structure that if you weren't at the top, you had to figure out how you fit in. So you see through the movie there are white people in different positions here. You've got the slave owner, you've got his overseer, you've got his drivers. But you also have other white people who come into the picture and that's actually a realistic portrayal because if you were in the South at that point unless you... and even if you lived in an urban area, even if you lived in a city, you could end up in relation to this in a similar way—you could end up working on the plantation next to some of the slaves, sometimes even doing the same thing. But there were social relations involved. There were people who were like: "OK, I'm in a low station right now but I am white so I'm not property. And there are ways to climb back up." And that's the socialization that people from that area go to.

But then in Bass you have someone who is there for some reason—physically he's there but he was not socialized into that. He came from somewhere where this was not what went on. I think slavery had been abolished in Canada some years before 1850, and I didn't know exactly where his outlook on the question came from. Because that's one thing I was wondering about, like: it's probably more than just he's from Canada that he's not into this thing. Because he was actually opposed to it and thought that it was wrong, and when asked by the master, he had no problem telling the master he thought it was wrong. Now, that's something Bass could do that someone owned by the master could not do without encountering a harsh penalty. And there's even been controversy amongst some forces of like: "Well, even in this movie where the story is about a Black man the agent of his emancipation is from this white guy that comes from outside."

Revolution: What's the controversy?

CD: The controversy is... it's kind of like: "Why couldn't the brother have gotten free on his own?" And the thing about it is... and you can see it in the situation of all the other enslaved people. Because even at the end there is... OK, Solomon gets out of slavery. But then there are all these other people. And if Solomon had said, "I'm going to take Patsey with me"... no, you're not going to take Patsey with you, and if you try then you're committing a crime because you're stealing legitimate property. And while you, Solomon, were illegitimate property because you were kidnapped into this as a free man, the kidnapping of Patsey's ancestors from Africa—"oh, that was legitimate, that was international commerce." But kidnapping Solomon was a crime within the laws of that time and that's why he could get out after those 12 horrific years. So it is kind of like people complaining about a true story.

And when I pointed it out to people, they're like: "But it still has Black people having to rely on someone else for their freedom." I'm like: "Come on, man, you've got a movie that puts slavery front and center, shows people exactly how it was, the brutality, the inhumanity of it, the illegitimacy of it, and is forcing that on to the front burner in the society whose roots and foundation are in that. And then you want to criticize the thing for depicting the actual way that this person kidnapped into slavery gets out?" Because it was... he was illegitimate property, but also, without a way to get that communicated to people who would come and act on it, he would have remained illegitimate property. Illegitimate, but property nonetheless. And that was the avenue through which his plight got back to people who then set in motion what ended up freeing him.

It was almost like for the people arguing this that it would have been better had he just stayed on the plantation in Louisiana because then this white man wouldn't have been the agent of his emancipation. Would you have preferred that he stay there?

Revolution: But that is also arguing, "why don't all white people remain enemies and nobody step outside of that role and do something to go up against it?"—that that's a bad thing when they do. Instead of when confronted with a situation like this where there was something he could do, the guy took the risk to do it.

CD: And it was a risk. It wasn't like... no problem, I'll go do it. I mean, you're in the South where this is the law and this is the system and you're stirring that up. If they find out that you're doing it you could end up dead.

But if people see the injustice in the situation and then decide they can't stand aside and let it go down, they have to stand with the people who are suffering this injustice—that's a good thing. This is a fine example. Put aside your post-modernism of "agent of emancipation" and whatever. This is a fine example. Wouldn't it be a good thing if more people who doubt they're the brunt of mass incarceration looked at it for the injustice that it was and said: "I cannot stand aside and let this continue to go down. I have to find a way to act." Wouldn't that be a much better situation than saying: "That's unjust but those people have to be the agents of their own liberation so I hope they pull something off," and standing aside and letting it go down?

And when you look at the actual forces that led to the end of slavery, they actually did involve more than the resistance of the enslaved people to that, and that was actually a necessary part of the process. I mean, people did rise up, there were slave uprisings, people did escape, but the overturning of the entire system of chattel slavery did require a war—one where the former slaves fought with heroism and died way out of proportion to their numbers.

Because the South was on some levels an armed camp... and it's in there in the film when Tibeats assembles the people and makes them clap and he sings that song about the paddyrollers. Well, the "paddyrollers" were the patrollers, whites who were formed into a militia that patrolled the areas around the plantations, and that poses to you how difficult it is to escape. Because it wasn't just that once you escape they would get a posse up and chase you—they would do that, but there also were armed white men in the area whose job it was to be on the lookout for slaves who were not where they were supposed to be. And in the scene where he encounters the two men about to be lynched, the guy looks at the tag around Solomon's neck—that was the permission from his owner to be off the plantation.

And that was a very real part of chattel slavery, you were really in an armed camp. There were these people who had that power to patrol and if they found you, you had to prove you were legitimately there or they could capture you and take you back or capture you and kill you.

The links to today

And it does bring to mind the police departments all across the country today, because it is still the case that for Black and Latino youth there is a bull's-eye on your back. And you might end up being used for target practice or you might not, but that potential is always there, that's something that people are looking at and dealing with throughout their lives. And that's part of what we have to get people to look at with different eyes in terms of the way that people can look back at chattel slavery and say: "Oh that's illegitimate, that use of force is no good, I'm glad we no longer do that"—but then not see that while it's not the same form, it actually does come down to... you know the Dred Scott decision—Black people having no rights that... and it's not just "no rights that the system is bound to respect," but when you look at Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, Jordan Davis, a message is being delivered that there's no rights that Black people have that any white people are bound to respect in this society, which is really the Dred Scott decision all over again. And that's something that people need to look at with the same eyes and understand the illegitimacy of the criminalization of Black and Latino people and decide that they cannot stand aside and let that go down.

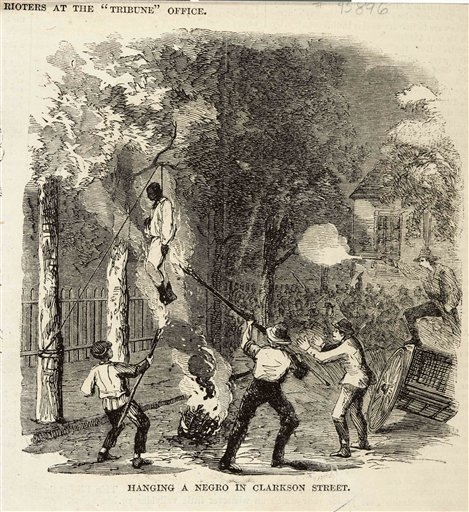

Depiction of a lynching in New York City during the "draft riots" in 1863.

Revolution: I notice that Steve McQueen, who directed this film, explicitly in some different interviews said that part of why he wanted to make this film was to draw the links between that history and the present day reality. He wanted to tell a story about slavery but he was linking it to, not just this is important history, but it's linked to stop-and-frisk, it's linked to all of the things that you were just talking about and wanting people to understand what's the roots of these things.

CD: Yeah, and that's an important part of doing this movie—the team that was involved in it. Because not only did the director say that, but the screenwriter did similar interviews where he talked about this story needing to get out. And McQueen was saying he wants to see it in the curriculum. People need to be studying this and understanding what it meant and what it means that this is the actual history of America.

Revolution: And there was that metaphor that the lead actress, Lupita Nyong'o, said when she accepted the Golden Globe—she said it's a look beneath the floorboards of American society.

CD: I think that's important to go at because this movie gets made and gets out there and is watched by all kinds of people. There is promotion of it for awards, including for several of the actors, best picture, all of this. And it does reflect that I think it is tapping into something, that some things are being revealed, and I think a lot about Bob Avakian's Three Strikes quote: This history of this country, first slavery, then Jim Crow segregation, lynch mob terror, and today a New Jim Crow—and, as BA says, "That's it for this system: Three strikes and you're out!" And linking them all and that they were forms of social control that served the ways in which profit was being extracted by those who ran the society, run this country. That that's been the history of this country—not one of continually expanding freedom and opportunity for all—and we need a revolution to get rid of it. It has been based upon ruthless exploitation enforced by inhumane barbarity that takes different forms in different periods, but, you know, you see the enslaved people chained together being marched to the auction block and then you see today's chain gangs that are being brought back in many parts of the country. And it is kind of like, that's the same thing, that's new clothes for the same body, new forms of the same thing being continued and there is a moment when people are looking at this and this poses a challenge, an opportunity for all forces in society. It's a challenge for those who run it to figure out how do we cover this back over and keep this shit going. But for everybody who sees this injustice and sees the current injustice rooted in the past injustice, there is a challenge to move to rip that further open, break through those floorboards more, to use that analogy, and show the rot that's at the foundation of this and to act to stop it and to get deeper into where did that rot come from, what's the source of all this, and what will it take to get rid of it. And that I think is very important to be brought out in general today in society and it's part of why we have to get Bob Avakian's voice and works everywhere, so that pole and possibility of revolution is out there for people when they do raise their heads.

Not: "Well, there was a problem and it got corrected and it's been a torturous path to correct it, but we're almost there and the arc of history has been bending completely toward justice." No, it hasn't.

The role of women

Revolution: One of the things that you mentioned that we wanted to get back to was all the different women characters in the story, both the enslaved women and the slave-owner women. What's concentrated in all of that?

I think there were a lot of different things. The first woman that we encounter is the woman, Eliza, who was actually kept by her slave owner, who treated her as his concubine, I guess, but had kept her in very nice conditions with slaves waiting on her and had children with her. And she gives a whole speech about this is how she survived, so she is completely unprepared for all of a sudden being thrown into the situation of being able to be bought and sold by other people and being treated the way... and that's the one whose children are ripped from her. And then you have Patsey. Patsey we should talk about, but let's talk about Eliza first.

CD: Yeah, because that was right towards the beginning of the movie and again the inhumanity of the system of slavery in this country hits you—this woman's children are ripped from her. She's sold to one master, one of her children is sold to another, the guy's going to hang onto her daughter, and posing that perhaps she's destined for sexual exploitation and repeated rape. But that is right at the beginning of the movie, and she is inconsolably devastated by it but then told you'll get over it in a few days. It again underscores that people were being treated as not human beings but animals. "We take the colts from our horses when they're born, why should it be different with you?" So there's that.

Then you're dealing with the situation for women enslaved on the plantation and the fact that... and this question of women's control over their bodies, which is still a question today in a different way. But for enslaved women you were at the beck and call of any white man that had some legitimate place in relation to the plantation that you were enslaved on—they could rape you at their desire and the only thing that would set up rules and regulations around it is if a more powerful white man had already marked you as his. Like I said earlier, other white men on the plantation knew they couldn't do anything to Patsey because she was Master Epps' property but then other women were fair game.

Revolution: And I also think what comes across and what was true in the whole system of slavery was that women were valued for their ability to produce more value. They produced more slaves which were then of tremendous value for the slave owners and then could be sold to make a profit. And Eliza had been in sort of a rarified situation where she had been allowed to believe, contrary to the way the system worked overall, she'd been allowed to believe that she had a family situation there where those were her children and she was going to be able to be with them and raise them. None of them were prepared for the reality of what their situation was because they had been in this rarified thing, but the truth of the underlying relations that actually were operating there came out because the master who owned her and had set her up in this situation was no longer her owner and then she became the property of somebody else who had no reason to preserve that situation. There's a whole speech, though, that she gives Solomon at a later point when he's telling her to stop crying for her children, and she says something like, "You're separated from your children too... and this was the only thing that was given to me in my life was to have these children and now that they're gone what's the point of my living? Here I am just a slave and there's nothing left." You think about that... you mentioned before about the tearing apart of the families but it wasn't even the case that most slaves were allowed to even consider the idea of family because even though people tried to bond together, and did bond together, that was totally at the whim of those people who owned them whether that was gonna be a situation that could sustain. And so when you think about all the great family values that are discussed today and how none of that had anything to do with even... women were breeders. But they were breeders as property and then producing property and that was it.

Thomas Jefferson with his slaves

CD: And people who were enslaved could marry and they could even have children but that was in the context of a system where they were property and the property relations trumped anything about families and so that children could be sold out from under parents or parents could be sold away from children or husbands and wives could be separated by the dictates of property. And that's what came down in the situation with Eliza and very sharply portrayed a feature that was at the foundation of America—the tearing apart of the families of the enslaved people because they fit into the needs and it was dictated by the property relations. And the point that you made about enslaved women having children was producing more value—that's actually very important too. I think the guy who did the biography of Jefferson, Henry Wiencek [Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves], made a point about how Jefferson writes in his thing, as he's cataloguing his property, he realizes that: "Oh you know the thing that really grows here isn't the tobacco, it's the people who I've got to work the tobacco fields." That's where the increased value is coming from, and Wiencek underscores that in his work. But that's brought to life in this movie.

Revolution: Then you had all these social relations that were built on this economic system where the slave owners' wives and children were all part of the slave owning class, but there were contradictions also between the men and women. The men had the power. The women didn't have the power except that they could exercise it in certain ways of either being kind to or cruel to the slaves that were underneath them. So there's a whole scene with Epps and his wife—Epps, the owner of Patsey—where he is blatantly going and having sexual relations with Patsey and flaunting this to his wife and she is furious about that. And at one point in the movie he tells her: "Well, I'd get rid of you sooner than I'd get rid of her." Now, all the reasons for that is what we should discuss—what was going on with him about it. I have some thinking on that. But her way of being able to deal with this is to take all the revenge not on him but on the slaves and particularly on Patsey.

CD: And to me what this book that the film is based on does, and part of why I want to read it, is again to see how this actually plays out, but it takes what was a feature of slavery and then depicts it through this particular slave owner and his wife and one of his slaves, a woman that he has an obsession for. Epps is kind of like: I gotta have her. And that is something, and while not every slave owner was out there with it, part of what brought it out was the offspring. You know, because the enslaved women start having offspring that are clearly not the result of their liaison with other enslaved people. Wiencek talks about it in relation to Jefferson, that there were all of these children going around who were half-white and looked like Jefferson. So even if you have someone who wasn't being flamboyant about it, the evidence is there. And it does become a thing, and it reflects the fact that the men did have the power and they could act on that power in that way and that the women had no choice but to put up with it and deal with it. And in this case they depict how it plays out between this slave owner and his wife. And you do see the way in which... because the whole society put the onus on the enslaved woman, both because the master can have her any time he wants at his whim, whether she's reluctant or not, and you see that in this movie where he does come to her, forces her and it's not being reciprocated, it's very brutal and coercive... this is one of the most painful scenes of the movie to watch. And on one level that doesn't matter because he wants her and "I own you so I have you." But then on another level it does matter to him because this woman is doing all that she can to make clear that I don't want you, I don't accept this even though I can't do anything about it. And that seems to drive him even farther over the edge.

And then the wife is like: it's your fault in relation to the enslaved woman, to Patsey, that my husband is acting in this depraved way. And she carries it out in terms of violence. But the overall societal thing was that this mythology, which also took the force of law, was that Black women were just hypersexual and on one level white men couldn't help themselves but on another level any sexual encounter was desired on the part of Black women. And where it made into force of law is that on top of the thing that Black couldn't testify against white people, a Black woman by law and custom could not be raped—because any sexual encounter was desirous. So charges of rape on white men for enforced sex on Black women did not happen.

Revolution: Even after the abolition of slavery.

CD: Oh, that carried into Jim Crow that that couldn't happen. And so there was a societal thing which is depicted in this movie, again in relation to the particular slave owner and his wife. And it does... it reflects the fact that the wife did not have the power to stop her husband from going to this other woman, but what she did have the power to do was to punish the enslaved woman for being the object of her husband's desire. And that does get carried out. And like I say, it reflects broader stuff in society at that point. And then even after slavery, because it continued and it is ironic that part of the justification for the lynch-mob terror was to keep Black men in their place, to keep them from violating white women when actually what was going on broadly throughout the society was the violation of Black women by white men. And you get through all kinds of memoirs, reporting from that time, that that was what was going on in a fairly widespread way, but terror being carried out the other way....

Revolution: With Patsey herself... you're watching the movie and it's clear that she's picking cotton at a rate over the top. She's a small woman and yet she's doing better than any of the men, and you're thinking why is she doing that? It seems like there's a certain way that that was the only way she could value herself. It was the only thing open to her that she could excel at this slave labor. So that's kind of excruciating on the one hand. And then you see Epps holding her up as the "queen" of the slave cotton pickers and there's obviously lust in how he's dealing with her. But at the same time he has to keep dominating her continually. And the obsession with her exists in the sense that she's his property. It's not that he has love for her, it's different even than the situation with Eliza where there's some regard for the person even if she's still kept as a slave. But this is just the most brutal possession of her, and then at the same time existing within the situation where he's not supposed to be... he is supposed to be but he's also not supposed to be doing this, if you see what I mean.

The way that he's so brutal to her... the scene in the movie where she comes back and says, "I only went there to get some soap because I slave away picking cotton, I stink so bad I make myself gag and the mistress won't give me any soap." I mean, the degradation of a human being to the point where you won't even give them soap to wash themselves, and you can just imagine what that labor produces in terms of how you would end up stinking and smelling from that labor. And to force somebody in such a degraded condition. And then he beats her for daring to—in his imagination—lust after some other man. It's not out of love for her, it's out of, this is my property and I can do what I want with it. It's one of the most horrendous relationships ever portrayed in a movie, I think.

CD: And I think it is obsession and it does have to do with "I own her, she is mine," and then it's compounded by her rejection of him. So you have this person who's enslaved and who is picking cotton off the charts. But that's not enough, and you do go and you force yourself on her but that's not enough either. She has to be a willing participant in it, she has to welcome this, and because she doesn't welcome it then he's gotta beat her down even, and invent that if she's not available to be forced into sexual relations or brutalized and degraded, well then maybe it's because she's after this other guy, this other slave owner who is obviously—they called him a Lothario. And he has a Black woman who he's treating as his wife.

And there is this obsession that drives Epps to further and further brutalize and degrade Patsey because of her rejection of his attention and there is no way that she can work through that. And there is a thing of that she continues to pick the cotton off the charts and I hadn't gotten at why is that. I think that might be what you're talking about, that this was somewhere where she could excel at something and do something she could do. She clearly could have picked less cotton and avoided the lash.

Revolution: With these slave owners, they have to keep trying to reinforce that the people they enslave are not human, but meanwhile they know that they are. This goes on throughout the whole movie in all different ways. In terms of the women in the slave-owning class, you have Mrs. Ford who makes the comment you mention: "Why are you crying, you'll get over it in a few days." She wouldn't get over it for years if her children were yanked away from her. But she doesn't see herself in the same category as this other woman—even though she's not cruel in the overt way. And then you have this other woman who's completely unsympathetic to any of the slaves and vicious because of the power relationship that's going on between her and her husband. And then there's Shaw's wife, the character played by Alfre Woodard.

CD: I did really wonder about that one. Because here you have on the one hand, master and mistress Epps and the cruel regimen that they enforce on all of the Black people that they've enslaved. Then you see Patsey over at the Shaw place being treated to tea by Mistress Shaw who herself is Black, and she's talking about: "I know what it means to be the object of the peculiarities of your master, but this is something you can work your way through." And it appears that she has worked her way through to the point where... she's called Mistress Shaw, and that's what's meant by treated as his wife. It isn't like she's just an enslaved woman he sleeps with, but she's called Mistress Shaw, there are other people waiting on her. So you have this situation and it is like you're seeing people in different ways trying to come to grips with a situation of being enslaved and here is a case of a woman who at least in this particular seems to have worked her way through it, and she's trying to advise Patsey on "here's an approach you could take—I know there's real problems with it but you could work through to something like where I've gotten."

And then you wonder, well, where exactly has she gotten because if Shaw croaked where would she be? Who would own her then? And what would that mean? But then the other thing is you're figuring that there's no way Patsey could work her way through to that because after this tea is over she's gonna go back to Epps who does have this obsession with her and is causing contradictions with his wife which gets played out in brutality directed at Patsey from his wife, and then there's the brutality that he heaps upon her because she does not welcome his sexual enforcement on her.

Revolution: I thought part of the situation with Mistress Shaw is one of these things where you've got a few people who kind of can work their way through the system to get into a better place. And it's being held up as maybe a way out of this which in reality is not a way out. It might be beneficial to that one individual but it's an anomaly to the whole system. You've got these millions and millions of people who are in this situation who are not going to work their way out of it through that. If you think about that in terms of today and how it's being brought up: you can make your way through this if you just try and you work it out and stuff. I wondered about what she was preaching and how that resonates in a certain sense with some of the ways things go today where a few people can make their way through the meat grinder and make their way out of it. I don't know exactly what their relationship was—her relationship with Mr. Shaw. But she intimates that she sort of figured out how to work him a little bit or something. I think that raises some questions in terms of women and how do women have to... in general but also women have to become pleasurable to men in such a way that maybe they can "work their way." You see a lot of relationships like that today. But what is the general condition of people? I was just wondering about... it's both the slavery question but also the woman question. It's worth thinking about.

Individual experience, broader canvas... and questions

Revolution: When you read the book, it captures more than just Solomon Northup's individual experience. He goes to pains to bring out the things that he observed and saw and all the different ways that this institution of slavery took place. He doesn't have a thorough analysis of what was underneath it, but you do get a picture of it. It does bring to life all the different dimensions of this bigger than just his own individual experience. It does make you think about how did such a system... how did all of it come together and operate as a system, as opposed to just: this happened to him and this happened to this other person. It leads you to want to go deeper into understanding that. How did they get away with having this system like this? How did they get away with treating people like this? And things are brought out that help you to question that and go more deeply into that. And that gets back to the question of what's happened since, and how did things end up the way they are now today, too. It brings in a lot of the dimensions of this—not by telling you about them in the sense of here's how this system worked, but by showing you in ways that I think make people want to think more deeply about how did these systems work like this. How did it all fit together? We were talking about earlier that the South was an armed camp but there were laws that were set up to reinforce the fact that the way they made society run and function was based on this extraction of value from these slaves—these people's value was to produce for the people who owned them and then that went into the market. So it's not like it lays all that out but I feel it does bring you to question.

CD: Yeah, it's actually in there, including the role of ideological justification through religion—that's in there as well with both the good master and the bad master quoting scripture as why you're in the place that you're in and I'm in the place that I'm in, and even the force that I use to keep you in place is rooted in the scripture.

And it's also another thing: "property reigns supreme." Ownership of property, including of people, but property is the determining factor. The ownership of property in one form or another is how the system works, private ownership of property. That takes a particular form of slavery, but it exists within the larger context of property relations, that that's how the society works—some people own the means of producing things and own the land, the machinery and the slaves. And that's how things are produced and those people get to benefit from it and other people are the ones that have to provide that for them. Whether it's the slavery then or later became share-cropping and other forms of it, it's all in that framework. I think...

Revolution: One thing I wanted to bring up is, I was talking to this Black woman who was telling me that she really didn't want to go see this movie because it just seemed too hard to look at this. And I think other people have said they didn't want to go see Fruitvale Station, which is the movie about the murder of Oscar Grant by the rapid transit police in the San Francisco Bay Area "because it was just too hard to see it and not feel like you have to act. And where are you going to act?" And I was just wondering what sense you have about that and how to speak to that.

CD: Yeah, I think that's important because, on the one hand... well, I was telling you the story earlier about when I bought the ticket to see it this time, the second time, there was a Black guy selling the tickets. And he gives me the ticket and he says "Enjoy." And then he says, "Well, I'm not really saying you should enjoy a movie about slavery because you can't really enjoy that. You know what I mean, man, right?" And there is that. It's a movie about slavery and it actually does depict slavery unlike Gone with the Wind that makes it appear like: "Oh, that wasn't so bad, in fact the slaves really liked it." This movie tells the truth, but you can't like that. That's not some shit that you could like. But people have to see it. People actually do have to confront that reality, and that's also the case with the murder of Oscar Grant in Fruitvale Station. And from one end, I wanted to see them both to see if they depicted that truth, and they did.

And this is truth that everybody has to see. Black people need to see it, white people need to see it, people of other nationalities. We all need to actually get the truth about both the history of this country in the case of 12 Years a Slave, but also its current-day reality which is spoken to very forcefully in Fruitvale Station. And people should feel like this is unacceptable—it was unacceptable that people were treated like that then and it is unacceptable that the treatment continues, although in different forms, today. And if you really got an ounce of justice in your heart, you should feel like you should act—act to stop this stuff because it is unacceptable. And look, I mean we're building a movement for revolution because things don't have to be this way. People don't have to be subjected to these horrors—whether it's the brutality and degradation that the slow genocide of mass incarceration and all of its consequences inflict on Black and Latino people, whether it's the immigration raids that tear families apart and disappear people, whether it's the denial of rights and brutality enforced on women, the government spying, the wars for empire, or the insane destruction of the environment by this capitalist system. All of that can be stopped through revolution and we're building a movement for revolution, and people need to get with that. And they need to take on these particular horrors. They need to be part of the fight to end patriarchy and pornography, they need to oppose these wars, the drone missile strikes, the government spying, and they need to be fighting to stop mass incarceration. And I think these movies contribute to a sense of questioning of this, both the history but also the current-day reality of the treatment of Black people in this society. And it's to me a very fine thing that movies like this... not only are they coming out but they're no longer kind of: one or two comes out and they're on the corner of things and you could maybe go to an art-show-type movie theater to see it. No, no—this is playing in the major multiplexes. That's a very big development and a very good thing because it is working on what people think and how they think about some very big questions. I know I've seen people online talking about: not another slave movie, I don't think I can go see it. No, you should go see this one. You should go check this one out because it tells the truth, and then spread the word and get others to check it out, including challenging people who don't know about this to come to know about it.

Revolution: I remember when Roots was being shown on television—it's a mini-series from back in the '70s covering the history of Black people—and what societal impact that had on people. And I think this movie is even more powerful than Roots in some ways. But I remember the effect that it had on Black people of feeling vindicated in the sense of some truth was coming out about what was real, and having right on your side of being against this and not accepting being treated this way in all the forms that it brings into the present. But also the effect that it had on millions of white people who did not know this history. It's been a number of years since that came out and meanwhile there's been tremendous assaults on any sense of right on the side of Black people and standing up against their oppression—all this bullshit about "reverse racism" and all kinds of things. Like "that was so yesterday, you shouldn't keep bringing that up." It's not like these films are films that are political tracts in a certain sense—these are artistic films, very artistically done, by the way—the photography, the quality of the filming, the acting and everything about it is extremely high quality. And that was... watching a second time that was brought home to me even more sharply, being able to watch the different elements of it. But films like this, and other films that deal with these kinds of questions, do have an impact in the thinking of people and the sense of what you were referring to of what's legitimate and what's not, what's right and what's wrong. And it's very important that there are works of art that bring that to people in this form. And I think it would be very wrong if this were reduced to this is just a good story about a guy who fought through adversity and ended up finally getting free. This is a story of a people, for one thing, but it's the story of this country. And I think... you know, from past times when things like this start penetrating, it both reflects that there's some divisions and some things going on in society where something is coming to the surface, but it also can have a major effect on the consciousness of people—not in a direct linear way, but significant nevertheless. And I think it's really important when such films are made that they be given this wide a berth of exposure, and that they be given awards and honors that help too... when they warrant them. And I'm hoping with these Academy Awards... I'm hoping that will be the case. But whether it is or not, it's important that people see these films and it's important that they have been given backing by people who are trying to get this story out. I think that's important. I feel like it's important to see how these things work into the mix of a lot of things, where you've got the awareness of Trayvon Martin and what that... you were bringing up Trayvon Martin and Emmett Till. The screenwriter, John Ridley, was bringing up that there's a lot of slavery going on in the world today actually, sex slavery and other forms of slavery, and that this is not... this form is no longer the form of it, but that this system is still producing this. So there's a lot of questions that are getting thrown up by such a film that I think is a very fine thing, even as it's excruciating. The excruciating character of it is something that should compel people to feel like it's unacceptable... I'm just agreeing with what you're saying that this is... not in the sense of you have to go out tomorrow and be in protest, whether people feel like they want to do that. But just challenging the whole way things are from the roots to present-day reality.

CD: Yeah, I think it does point to a different way to... it brings to people some things that a lot of people don't know. And then even people who know them, it matters that this is being spread through society and it gives more of a sense of right on your side and legitimacy in the way that you feel. I guess what I'm trying to get at is it's a different way for people to think and feel. And that's actually very important. It isn't just: well, can you get people to do something, but what are people thinking about, what do they understand, and how do they understand it, and how can that be transformed. Because we do have to go... just like you had to go from a point where that setup, that system of chattel slavery—with human beings outright owned by other human beings and treated as property and beasts of burden—had to go from that being seen as legitimate to that becoming seen as completely illegitimate. Well, today we have to tear away the legitimacy of the New Jim Crow and the slow genocide that's strangling the lives of tens of millions of people, and move that to the point where people are seeing that and all these other horrors today and the capitalist-imperialist system behind them as totally illegitimate.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.