From "Bombingham" and Selma to 2015

Interview with a veteran revolutionary

March 2, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

This is an interview with Hank, who grew up in the South—about his life and struggle under Jim Crow as a child in SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) at age 11-12 in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963; running away to Atlanta at age 15 and joining up with and becoming a revolutionary in SNCC (Student National Coordinating Committee); how later he became a revolutionary communist as he sought the answers for how to end the oppression of Black people and emancipate all humanity. What he says has a lot of lessons for today.

Hank: I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and some of you might know it was also called “Bombingham.” My family owned a small business. We lived right across the street from the First Baptist Church, which was the church of A.D. King, Martin Luther King’s brother, and at that time there was a lot of bombings going on in the city and stuff.

There was a neighborhood called Fountain Heights, and it was a working-class white neighborhood that people began to integrate. And as Black people moved in, people’s homes began to be bombed. It was later nicknamed Dynamite Hill because of all the bombings, so this is almost like a constant in terms of some of the things going on in the city at that time and everybody, whether you were a little kid or an older person, you lived with that kind of fear that something like that might happen. So that was part of the atmosphere you grew up in on the one hand, but then on the other hand while it was very turbulent, it was very exciting because there was all this stuff going on that people were resisting, so in that sense it was exciting.

Again, growing up in Birmingham during that era, the question of the fear and brutality, you saw that all the time. Most people are aware of it in relation to the demonstrations, with the dogs, the water hoses, things like that—but there was also the constant brutality of people being beaten by the police. Fair Park was one of the places where they used to take the youth. It wasn’t open, but they would take people to Fair Park and actually beat them there. It was part of the atmosphere and you were actually taught how to respond to police and white people because of all of that. Your parents cautioned you about this and when you did things; one of the things I will never forget is my mother would tell me: “I will kill you before I let these white folks kill you.” I took it at the time that she actually meant it from the standpoint of that being a reality for youth growing up at the time.

Revolution: What was it like when you did things that kids like to do—sports, swimming, movies, all the things that kids like to do?

Hank: I thought everything that was going on was normal. We went to the movies but when we went to the movies white people sat in the main theater at the bottom and we sat in the back, at the top. I enjoyed sports and excelled at them pretty much. The only integrated thing that was going on at that point was at the swimming hole. This is the place we called the Big Ditch that bordered the white community and the Black community, and both white and Black youth would swim there, but it was also you had to fight each other to actually be able to do that, so there was always some kind of confrontation between Blacks and whites. Part of the life was not just the official stuff but just what was going on in everyday life, the interaction and how you confronted white people and how white people confronted you. You got tested in a lot of forms of confrontation, particularly among the youth at that time. Sometimes it got really, really heavy, and other times, being youth, we actually thought it was just a lot of fun.

I grew up actually hating white people and hating the system of Jim Crow. We were talking earlier about the swimming hole and having to fight through that. I remember one time we got into this fight with these white kids and I was beating the shit out of one of them, and all the while when I was doing this, he kept calling me a “nigger.” And I tried to take some dirt and just stuff it in his mouth and even after he spit it out I was still to him a “nigger.” That had a kind of impact on me because growing up back then, you say “uncle” and you give up, but there was no “give” and the impact of how deep this stuff was, that had an impact on me. It seemed like this stuff is ingrained in people and in one sense—what do you do? Even as you’re kicking ass, it doesn’t go away.

Around ’64, I remember the Mule Train came around with all these different people from around the country. They were part of the civil rights movement and I remember them coming to our church. Our minister was head or one of the heads of the SCLC chapter, and all these different people, all these different nationalities, they came with the Mule Train and they parked at the park where we played baseball, and this was the first time I actually began to get a sense of how all white people ain’t the same. That really had a big impact on me because the hatred I had in seeing white people as the enemy began to reshape. It began to get changed, and that also meant a lot to me that people came down and was willing to stand up with us, and not just stand up, but with interacting with us in the church. And I saw how they were interacting with one another and it was real genuine and it made you feel like you wanted to be a part of something like that. I thought that was part of something that was really, really important.

Revolution: Could you describe how you got drawn into the movement?

Hank: It was mainly through the church. I come from a very religious family, and again being from a little better off family, people have certain expectations for you. Even as a youth, as early as 11, I was a Sunday school teacher. One of the things in my life that was different than a lot of my peers is we grew up with books. We grew up with encyclopedias. I began to read early on. At a certain point I had read the Bible all the way through, and I was very informed by religion and certain things about fighting against evil, fighting against injustice. For me, I got a sense of that from those religious kind of views. SCLC had a youth organization, and part of the thing we did was we went out in the community. We knocked on doors to try to get people to be registered voters. That’s part of what you did and that was a lot of fun. I remember going to one woman’s door, which also had an impact. This was an older Black woman, and she actually slammed the door in my face. But before she did she told me to get away from her door because she didn’t want these white folks bombing her home. And the way she said it and the look in her eyes was very, very troubling because you saw the fear that she had. And at that point I made up my mind that I will never ever live like that. I can’t see myself being this old woman living in that kind of fear.

Revolution: What did you say, and what kind of arguments went on in your house about this?

Hank: In my house you didn’t argue. My house was ruled by the whip. What they said was law so you didn’t argue; you just took the lashing. You did what you were going to do and you took the lashing.

Revolution: Even to go out and try to register people to vote?

Hank: I could do that. That was supported by my family because it was not seen as the same as demonstrating in the streets.

Revolution: So if you went to a protest you would not only face Bull Connor (police commissioner of Birmingham, notorious for his brutality) out in the street, but when you got home, you would be whipped?

Hank: Exactly, so that was somewhat of a deterrent but it didn’t stop me. This was around ’63. Every year up until the time I actually went to high school they would have these walk-outs. They would walk out, they would stop at every school, elementary school or high school within that community, until people got down to the Kelly Ingram Park (next to the 16th Street Baptist Church), which was about five or six miles from where the high school is, and I couldn’t wait to get to high school to be part of the walk-out. But the anticipation of being them coming to my school, it was there. I never saw any adults as a part of this. It was very organized in what they were going to do and nobody [teachers] put up any resistance. It was open, and many kids went on down; some went home. At a certain point I watched, then at another point it was kinda like, “I don’t care.” I would go on to the next one and end up at Kelly Park.

There would be a march and demonstrations; sometimes nothing happened. And in some instances you would be met by the police, the water hose, the dogs. It was my first opportunity to actually be a part but also witness first hand the kind of cruelty and brutality that was going on, and I made a point not to try to get arrested. I had some older friends, and this was important to me; they took me kind of under their wing. And they were on the sidelines, and they weren’t into a whole lot of the non-violent philosophy themselves—and actually they did do a lot of stuff with rocks and the bottles, and I would say they were considered “the unwelcomed.” But they were part of that movement that actually came down there, so I never took an arrest in any of this, and part of it was we were on the sidelines hurling different things and stuff. There was a saying, “If you’re not going to be non-violent, don’t get in the demonstration.” These older kids weren’t having it. They weren’t gonna just allow themselves to be brutalized and this and that and the other. We might have gotten wet, but we didn’t take the brunt of this, and we weren’t in the crowd but we were on the sidelines. But these older kids were actually hurling objects at the cops and trying to fend them off in relationship to what they were doing, brutalizing people.

Revolution: Did you believe in the non-violent philosophy of SCLC and Martin Luther King?

Hank: I was never non-violent and my house was never non-violent. This is some of the contradictoriness.

Revolution: Can you talk about the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church, which was adjacent to Kelly Park and it was a big center of the organizing, including of the youth who were taking part in the demonstrations? This was the 1963 bombing that killed the four little girls and injured many others.

Hank: My memory of the church bombing was that the whole community was both in shock and grief and at the same time outraged around all of that. Even right there on the spot there was escalations of things between the community and police. I know that in the community I grew up in, the police actually did go to A.D. King’s home, supposedly to protect him, and people actually set fire to the police cars.

While there was shock and grief, there was a lot of anger, and that poured out in different ways. I’m not sure all the different ways, but I actually do remember that was one of the things that was also re-broadcast on the news after that happening. And that was a certain determination of people that “this shit has to end,” “this shit has to stop.” I think it emboldened more people, and even people who at a certain point were opposed to this kind of stuff. When I say opposed to this demonstration and it was stirring up more people who couldn’t sit by and watch children being bombed in worship. I think that had a big impact in bringing more people into things and also solidifying people’s commitment that this stuff actually has to stop. If you think about that period and you think about what transpired afterwards, I think that during this period the whole question of people actually really, really looking for something different. And this is the first time I began to question god.

Revolution: When the bombing of the church happened it made you question god?

Hank: My thing was “why is he letting it happen? And this is his house, and these kids hadn’t done anything so why are you doing this?” Because I was born a religious person, I used to have nightmares about even the thought of questioning god. It wasn’t all thought out but I just knew it was wrong, and he could do something about it if he wanted to and I couldn’t figure out why he wanted this to happen. I was maybe 11 or 12. It was these things and it was very troubling for me because even up to the time I ran away from home, I was on my way to church when I ran away from home. Church was a constant. I don’t care what stuff I got into, every Sunday we left home going to church; that was one constant.

Revolution: Can you talk some more about what it was like among the youth?

Hank: A lot doesn’t get told in a lot of these documentaries and things like that. I remember seeing a scene from Eyes on the Prize (from episode 4 of the documentary film, available online) and one of these SNCC organizers was getting ready to go to a demonstration, and this was a demonstration when mainly a lot of the youth were involved. So he ask them, “Before you go, everybody empty your pockets.” And one of the things I saw, and I laughed about because it was really, really consistent with what was going on there... Everybody started emptying their pockets and you had all these pocket knives that was lined up on the ground. And one of the things you don’t see when you look at these films about the attacks on Black people in particular, the dogs and the water hoses, you don’t ever see the scenes where people are actually stabbing the dogs, slitting the dogs and stuff like that. This doesn’t get shown and I do think that has something to do with not seeing how people actually did go up against it and what that might inspire. This is not what you ever see in terms of how people responded back, in one form or another. And people talk about the “riots” where people en masse actually did those kind of things but then there were all kinds of confrontations that went on all the time. There was the “official” version of the struggle against segregation in the mass movement, but then there was daily life in which people confronted and had to confront different things in different ways and a lot of it actually did consist of fighting back. People would try things. Youth would just try things on their own. We would go to a bowling alley where we knew we shouldn’t be because it was all white, and we’d go in there and confrontations would break out and we’d get in fights and we’d get chased out of the neighborhood. We would go to white recreation centers and challenge people there and get into things. Now none of this was “sanctioned” by the movement, but this is what’s happening among the youth all over the place and it wasn’t just the crew of people I was involved with. It was just part of testing the waters and actually saying “all right, we have a right to be here and we’re gonna be here and so be it.”

You would go some place like this all-white recreation center; we’d go there and people would be treated a certain way, and we would get our little group and we’d just march around the outside singing “we shall overcome” and daring anybody to mess with anybody out doing that. This is not by the church. This is not by SCLC. We did those things as part of; a lot of it was just in defiance of the official movement and a lot of it had to do with how older people approached things. I think there was a lot of defiance in what was going on, but as youth we wanted to express in our own way.

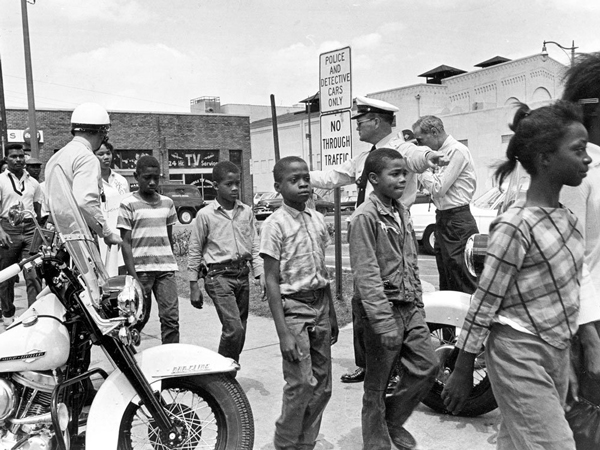

May 1963: Birmingham school kids are taken to jail for protesting discrimination against Black people. AP photo

Revolution: Can you describe how your thinking developed and changed as you got more deeply involved and as the movement itself was coming up against bigger challenges and questions?

Hank: There were some things that happened that were very significant. One was the whole question of seeing that there was a system, a Jim Crow system, and not white people that were responsible.

Revolution: How did you make that change in your understanding?

Hank: It took some time and a while, and part of it was the first thing was to actually look at, in my mind, this is how I looked at things: Bull Connor was white, the policemen were white, the firemen were white, George Wallace [governor of Alabama] was white, the people who owned these stores were white, and these were the people who were denying and messing over Black people, oppressing Black people. Everything I saw pointed to white people as being the problem. There was nothing, Jim Crow or other things, that didn’t point to white people, so I grew up thinking the problem was white people—not that it was the system of Jim Crow, it was their system.

When people came on the Mule Train—people from all over the country of all different nationalities—you began to question: Is this all white people, or is it just some people? Is this all white people in the South, or is it that white people from the North are different than white people in the South? Because you didn’t have, that I could tell, anyone in the South, white people who were actually supporting what was going on. And part of this was you ran the risk of being brutalized and murdered as well, so you didn’t have that open kind of thing. So I began to see at least not all white people are the enemy. Some people will stand with you, and this, that and the other.

Revolution: Did you have views about the role of the federal government at that time? You were describing to me that when JFK was assassinated, everybody was crying. Did you have a hope or expectation that the federal government would come in and intervene and force George Wallace to back off segregation?

Hank: I wouldn’t say it was my expectation as a youth one way or the other; I do know that was the expectations of our parents. I do know for myself as well as most Black people at that time, Kennedy was seen as a friend and someone who was working to actually help Black people overall and in particular in the South this is part of the persona. I know right after his assassination there was not a Black house I went into, including my own, that did not have a picture of Jesus and a picture of Kennedy.

Revolution: Selma. Were you aware of that when you were in Birmingham in 1965?

Hank: These are things that actually hit national news.

Revolution: Did it have any effect of making you aware that this was not just a problem in Birmingham or just a problem of Alabama, but it was much more extensive, or did you already know that?

Hank: We knew what was going on in Mississippi, what was going on in Georgia. We used to have these things with kids from other states who would come and visit and talk. We knew who the mayors were and who the governors were. We was talking about the hatchet-toting governor of another state, “at least our governor don’t run people out of the restaurant with hatchets.” Because it’s televised, it’s really out there. So you get some history of what’s happening in Mississippi, what’s happening in Georgia, Little Rock. Unless you’re just not keeping up with things, you have a very good sense of the connections between what’s happening to Black people all over the South.

Revolution: In the wake of that you began to see H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael from SNCC on the news, what effect did that have on you? And on others around you?

Hank: It had a real positive effect. One of the things is that they weren’t calling on people to be non-violent. They weren’t calling on people to be calm. They were actually telling people they had the right to stand up and fight. For youth this was different than “turn the other cheek,” and it was articulated from the standpoint of the need for people to actually stand up. I was still torn. Torn between whether or not you could actually change anything. And then my religious beliefs about putting things in god’s hands. I could understand that what happened to Black people was wrong and nothing could deter me from that understanding and the need to act on that. That in itself begins to get to a lot of questions. This is when I hadn’t met “non-believers” or atheists. It was not until I got into SNCC that the whole question of whether there was a god or not a god was even being raised as a question.

Revolution: When did you leave Birmingham?

Hank: I ran away from home when I was 15. There was this friend; I always hung out with older kids. He had graduated from high school and was working in Atlanta and he came home for the Thanksgiving holiday and I made up my mind because I was kicked out of school for having sideburns. This was1967 and the school is an integrated school at that point. It was kind of ironic that because I had sideburns, I’m kicked out. Then you had the Beatles all around the school and you had all the white kids with the Beatles kind of looks but we had to cut our sideburns. I got kicked out for not cutting those. It was a bunch of racist bullshit, but I was also fed up with everything that was happening there.

I wanted out of the city and my home and Atlanta was an opportunity.

So I went to live with this friend in Atlanta, found a job and worked with him doing yard work in one of these rich suburban areas of Atlanta. Up the street from us, there was an H. Rap Brown Community Center. And it was just that—a community center where they had it open to kids. So we used to go there. We were very athletic, and we liked to do stuff and we went there and played ping pong—and we start talking. People would start talking about what they’re about, what they were doing and eventually I end up joining SNCC.

In Atlanta, there was a movement that was different than Birmingham. Birmingham mainly consisted of the civil rights movement. In Atlanta, you had the Black liberation struggles and a lot of organized nationalism. I am very much into the streets and fighting, but all the different trends, as we call them today, and all the organizations that existed back then—I am new to all of this. And in SNCC, it was a mixed bag of people. In its main character it was students from Morehouse and Spelman [two Black colleges]. There was also Black intellectuals and intelligentsia who was all a part of this. They were debating all kind of stuff going on in society from all kinds of viewpoints, and it was really new and exciting and it had a very militant and radical edge to it. In that process, I became more radicalized, to even begin to grapple with these big questions going on in society. If you look back in Birmingham and the movement there, it was a different feel and mixture of things. The question of how to end oppression of Black people was very widely debated in Atlanta and nobody was putting forth elections or voting in that circle. But there was a lot of reformism nonetheless. One of the things that still sticks in my mind is the question of land for a separate Black territory: Black people can only be free if they form a country. So autonomy for Black people in the Black Belt South was one of the questions that was being widely discussed. These were not things on the agenda in Birmingham. The kind of political climate that existed in Atlanta was so different even on a cultural level—so much more sophisticated. This is the beginning of me being introduced to radical ideas and solutions. Before then my framework was the civil rights movement, so this opened up a new way of looking and thinking about the world.

At that point they were the Student National Coordinating Committee. When I joined SNCC, they had both changed their name [from Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee] to more reflect their break with non-violence, and also at that point they had kicked out all the white people that was in it, and in that sense it was more of a nationalist organization, but it had a lot of ties with a lot of different groupings. I remember people debating over whether or not it was the right strategy, and part of the people were saying that because of the white purse strings it made them have to cohere to a certain kind of view.

Revolution: Earlier you mentioned further questioning your religious views as you were getting involved with SNCC. Can you talk more about that process?

Hank: It was people raising the right questions, as BA would say. If there was a god, why would he do this? Why would he do that? If he could stop all this stuff, why doesn’t he? People were actually challenging me to look at my faith and my belief in god and say, “why?” And people (believe me various people with different views about why this stuff is happening) did point to that the only reason this stuff is happening is because of the system of Jim Crow. And I got a deeper sense of Jim Crow and the laws, etc. These people were very factual about different things and could point you to different things about the system and it raised more questions. This is where the whole question of white people begins to get raised. It’s not just white people. It’s the system. You get rid of the system. Racism is used to enforce that system.

And then my thinking became, “I’m going to live my life as a righteous person. I’m not going to do certain things. I’m not going to be a bad person.” In other words, if I am wrong on this question then you have to judge me on the merits of what the fuck I do. It was a whole long process, and like I say it took a long time to really, really make the rupture that there’s no superior being, there’s nothing out here but matter in motion. That’s beginning to come into me getting into Marxism and Mao.

Revolution: What was being involved with SNCC like?

Hank: Actually I became a revolutionary in SNCC, and one of the things was that we were much more radical. One of the things I remember—at the national office, we got communiques from all over the world. We got the Peking Review, we got the newsletter from Cuba, we got stuff from Vietnam, we got all kinds of communiques came to the national office, in bulk. It was in reading some of those things; it was reading the diary of Che in terms of the Cuban revolution. At that point SNCC itself in character was more and more leaning toward revolution as being the only way out of this and it was very diverse and I actually remember a group of us wanted to get training.

I had a lot of respect for H. Rap Brown. He was somebody who had a profound impact on me and this question of leadership was really, really a big one. One of the things I remember is when he went underground and when he reemerged (he was shot and spent a few years in prison). When he came out of prison he was a Muslim. And I saw him. He came to Atlanta and he opened up a boutique shop selling incense and this and that. And I was devastated because this was somebody I looked to for leadership, this was somebody I would follow to the end of the earth and he was in this boutique shop. I went to confront him about that. At that time I saw him as selling out. And we had some very heated words and it almost bordered on fighting. I just remember leaving there disgusted. It took me a long time to get over this. This is something that BA helped me understand when he wrote this thing around Huey—about there being a limitation to people’s understanding, that they can only go so far because of their understanding of what’s needed and how to get there. It took me a long time to actually not feel ill feelings toward H. Rap Brown because of what he came to represent. Again, the way BA talks about this helped me a lot to view this differently. BA talks about this in terms of what these people were running up against. This actually helped me view this differently and put it in another perspective and even to appreciate who H. Rap Brown was and what he was during those times. Not to become them or to use this as an excuse or that they couldn’t have dealt with this in other ways, but at least to have more understanding of what they were running up against. At a certain point you develop these views towards people who were in the movement that they are either sellouts or traitors. That’s a hard thing when it’s people who you actually looked up to.

Revolution: How did you go from being a revolutionary nationalist-minded person in SNCC to becoming a revolutionary communist?

Hank: I met these two guys when I was in SNCC. These people introduced me to Mao and Marxism and again it was through the Red Book. They were always quoting Mao.

A friend took me under his wing and began to get me into Mao, and they both often talked about Lenin and Marx, but I wasn’t quite ready for what we called back then “European philosophy” [Marxism]. Mao I could deal with, but “European philosophy” I wasn’t quite ready for. It was in early ’70 that he and another SNCC staffer were on their way to a trial of Rap’s in Maryland and they were killed in a car bombing, and that was a big, big thing for me. The authorities were trying to say that they did it to themselves. They were trying to say that this was connected to some sort of act of terrorism in relationship to Rap’s trial that was going on, which was totally bullshit. Everybody who knew these people knew that was not even a remote possibility. They were killed by authorities and that was a big blow.

Coming through the movement, you got introduced to every kind of philosophy out there; in terms of the nationalism. There was revolutionary nationalism, which is part of what SNCC was, a revolutionary nationalist organization, who saw the struggles of Black people as essential of what they were fighting for and about. There were Pan-Africanists, who saw the Black people’s struggle here connected to the “motherland” of Africa, and that Black people in this country or anywhere around the world could never be free unless the motherland was free, and this is something that Stokely actually became a part of during this same period. There was the cultural nationalists, who saw the only way of struggle was through culture—and a lot of the culture was really, really good, but a lot of it was divorced from changing the world. And then you also had what I guess we would call “pork-chop nationalists”—this was just a weird form of nationalism that saw everything that was going on had to do with white people, Yakub was the devil. It had something in common with the Black Muslims’ view that white people were the devil. But it was mixed in with the dashikis, with the culture, and a whole lot of mysticism along with it.

And the reason I’m raising all this, is all of this was a kind of framework that the movement was a part of, and I was a part of, and everybody was putting forth all these different views, even SNCC itself was a mixed bag of different philosophies. And Atlanta was a kind of center, particularly for the cultural things that was going on. Atlanta was similar to Harlem in that sense. It had a very large Black middle class in Atlanta, even at that time, and there was a lot of influence on the movement. It’s like you had all this “Blackness,” you know what I’m talkin’ bout?—that was resonating in different kind of ways. I was affected by a lot of that, and you just had to sort through what was bullshit, what was not, what was good. Again, there was a lot of struggle, and there were key individuals who played an important role in me doing that. It was trying to get a sense of what the problem was, what was the real problem. Do we need revolution? Do we need some kind of reform?

A lot of questions that came up in Ferguson were a lot of the questions that came up back in the day. And a lot of the resolutions being put forward—police review boards, more Black policemen, more Black officials—all these things being put forward as the ways to resolve things, a lot of this shit affected Black people.

Revolution: What convinced you? Because certainly some people pursued that other road—for instance, John Lewis left SNCC to become a congressman. What influenced you to decide that wasn’t the answer?

Hank: I just thought that this system wasn’t reformable. I just thought that what it actually did was really fucked up. And mainly it was coming from a Black perspective: what was the whole history of Black people in this country? That there’s nothing it’s shown me, in this country’s history that said that anything other than revolution would reform it. Now what kind of revolution? This is the thing about not being scientific and not having a real understanding of shit. This is where again, and BA really hammers on [the limitations of this view]... this thing about “all we wanted to do was get rid of this, alright? Get rid of this, and then we’ll be in power.” And I think this has a lot to do with two things: revenge, and also this is part of the church shit in a way, the thing about “the last shall be first”....

Revolution: So what began to convince you, how did you go from where you were there, to actually getting connected up to revolutionary communists?

Hank: I was for socialism. That communism word had a baaaaaad connotation for me, OK? I want to make revolution, I want to make socialism, and socialism is more acceptable to me and where I was. And again, I started reading about socialism. People started to go different places. People went to [revolutionary] China, people went to the Soviet Union... and then they’d talk about these things.

But it was through reading Mao—and this is one of the finer things about Mao and nationalism: you’re reading this Chinese guy and you know that they kicked ass over in China, and all these great things in socialist China, and you’re reading this, and this guy is always quoting this white guy! And these white guys [chuckles], Marx, Lenin, Engels and Stalin. And the more you’re reading, and see the influence that they had on him, and the more you’re internalizing who he is and what he represents, you have to come off of some of your nationalism. You had to begin looking into what they’re saying. You had to begin looking into whether or not this is where I want to go, and this is where humanity needs to go. And this is not a one-step process, because you are actually beginning to rupture with the way you are looking at different things.

Revolution: In relationship to this, how did the struggles round the world and that whole environment influence what you were thinking?

Hank: It had a big impact. Everything that was going on in the world at that time. There was the Cold War that was going on, and there was the Vietnam War going on, and there was more and more resistance to that. You can have two thoughts at the same time. I had a deep hatred for Jim Crow and how this system treated people; at the same time, there was feelings of patriotism about defending the country against the threat of this communist thing... the threat from the Soviet Union and the Vietnam War being the “spread of communism,” and all of this.

My best friend got drafted into the service, and instead of going into the army he volunteered for the Marines, and I actually said I was going with him. It was the buddy plan we were goin’ on, I had to get my parents to sign and all of that. And it was through a lot of struggle with people in SNCC, up until the day I was supposed to meet my friend at the induction center, I was still going. And there was a lot of struggle with the people in SNCC about what this war was about, what it represented, and they showed me this picture: if I remember correctly it was a call from the Vietnamese people to Black soldiers, and it resonated so much with me. It said, Black soldiers, am I the one who bombed your churches, raped your women... in other words, it was painting a picture of Birmingham, and the history of Black people, and why are you over here fighting? So... I didn’t go! This is the power of ideology, and how you understand things, and how different things can be working on you. I wasn’t quite in “solid core” at that point, but influenced by all kinds of things, including personal relationships. This guy was my best friend, and I’m not gonna lie, there was a certain kind of thing, growing up under “John Wayne” kind of shit that was an influence, so that was a process going on of breaking with all kinda shit.

Revolution: So this is the atmosphere where all these big questions about the nature of society and social relations are being struggled over, and at the time you left SNCC and joined the Black Workers Congress (BWC), people who considered themselves Marxists and communists, but combined that with nationalism (my people first). Can you talk about that and then later why you left BWC and joined up with the Revolutionary Communist Party led by Bob Avakian?

Hank: This is where I undertook to study more Marxist theory. It actually began to take hold. There was all these different organizations in society and in the world. I remember reading Mao. And you read about different things the Chinese revolution was doing, you read about different things happening in the international arena, but it was hard for me to ever [find] things where he didn’t talk about the need for a party and the role that a vanguard party played... and this was something that I think a lot of people began to grapple with. If we were going to do what we said we were going to do [make a revolution], how were we going to do it with these different groupings? This was the question in my mind and I’m sure in other people’s minds. I do remember at a certain point the Revolutionary Union [the forerunner to the RCP] was trying to coalesce different groupings to develop a vanguard party. You know, you like to think that you were, even when you weren’t. Then you face the hard reality: if you’re a nationalist, is there something wrong in relation to being a communist? And what is a communist? So even the question of becoming a communist, there was still the rupturing with nationalism. And I do remember the struggle over this...

Revolution: You’re getting into very interesting questions. Among young people coming up there’s the view that people’s life experience is enough to understand the world, they don’t need any kind of “outside” ideology; that Black people who have suffered this oppression are more capable of understanding where this needs to go. What did you come to understand about all of that, and what would be the implications for the youth today who are grappling with some of the same questions about how to get out of this?

Hank: I do think for a lot of people, including myself, people do have experiences that do reflect a lot about not just what happened to them but the oppression of Black people—but even how you see that and sum that up actually takes more than your experience. I’m not downplaying the role of experience in all of this. But understanding where all this is coming from and what is possible—it takes theory, actually. [Your experience] is not enough to understand all these different things.

People are responding, in this country as a whole, to the oppression of Black people, in particular to police murders [of Black and Latino people]. This is really important. And there are a number of different things that are actually being put forward as a way to resolve a lot of these things. Until I got a basic understanding of what is the problem in society, what is the solution, what is it actually gonna take to end all this, and not just for Black people but for humanity as a whole. If you don’t have that as a framework, it’s like Lenin’s quote about how until people get an understanding of different class forces and their views on things, people will always be victims of deceit and self-deceit.

And that’s the role that theory plays: It actually enables you to understand the world. It’s not like people become conscious, and all of a sudden, that’s it. Even when I really believed I was a communist and had some sense of internationalism, for many years the question of revenge was still there and part of that was not having a solid understanding of where things really need to go and how to get them there. Because remember earlier we were talking about seeing socialism, and the first shall be last? All right, part of the thing is just getting to there. Part of the view is that that’s enough. And in my own mind, as a communist, I was still wrestling with these questions, and all the connotations.

There were a couple of things that I think were important to really becoming a communist, and part of the Party. Most of us had come to understand that if you were going to make revolution in this country, you were going to have to be part of a vanguard party, multinational in character, and that was a driving force. Even though there were contradictions around “Black workers take the lead,” there was still an understanding that we needed a party if we were going to do this.

I remember a group of us actually went to hear this debate between Bob Avakian and two other people. And it was all on this question of party-building. The other two people were leading figures of some group. They all gave presentations, and I remember a discussion of it afterwards, and the profound impact Avakian had on us as a group and this had a lot to do with us proceeding forward to be part of the coalition to debate these questions out.

Revolution: Could you talk about that—“Black workers take the lead”—what was wrong with that view, and how did you come to that conclusion?

Hank: Well, we were certainly looking at things from the standpoint of nationalism. We understood some of the context of the need for a working class, the proletariat, to lead all of humanity to emancipation, we had some understanding of that, but also for a lot of us—and it would come out in SNCC—there was still a lot of distrust for white people, and if white people were the fundamental people who were leading this, then it would lead to something that would not be good. Part of it was that in order for this to actually go anywhere, it was essential, from our perspective, that Black people play a leading role.

But that didn’t comprehend the most far-sighted vision and understanding. Who represented that is what should lead. What understanding could actually transform things for humanity. Eventually some of us, a small minority, actually came to that. Carl Dix, one of the founders of the Revolutionary Communist Party, who was also a member of the BWC at the time, often talks about his all-nighter, his encounter with BA—and he was a founding member of the Revolutionary Communist Party. And others of us, we took up revolutionary communism later.

It was understanding that this IS the way forward, this is the right thing to do, and also, again, breaking with some of the nationalism, becoming more of an internationalist. When you’re looking at things through the prism of your own nationality, then everybody else gets left out. Your struggle becomes more important than the struggles of the farmworkers, of Spanish- speaking people. You’re proceeding from what you have “invested” in all of this, in a sense... because most of us came forward in response to what was happening to Black people, and you sacrificed quite a bit, including time spent with families and friends. But once you understand you’re doing this as part of all humanity, once you understand that you’re doing this as part of ending everything that you hate, not just for “your people” but for the people of the world, it means more. And there was other factors: you look at the tremendous sacrifice and heroism of the Chinese people, what they were doing to support liberation struggle of people all over the world, including of Black people, their view towards internationalism, then you have a responsibility, if you consider yourself to be a communist, to proceed from that. Understanding that this is about humanity, about ALL the horrors—this is really important.

There was a lot of documents circulated among us and there was a lot of struggle in the BWC. And again, only a few of us went, but it wasn’t just by ourselves, there was a lot of struggle, Red Papers and other papers were circulated, and people even wrote replies. It was serious, and people took it serious. I think those who did join the Party actually made the right choice.

Revolution: If you were addressing these youth today, in the middle of this mushrooming struggle against the oppression of Black people, when people are saying here we are, 50 years after Selma, people look back on the courage and sacrifices that were made then—and even the Black middle class is somewhat saying, some of us may have done OK in this past period, although nobody escapes what Black people are subjected to in this country; and a lot of youth are for the first time raising their heads and saying this is a horror show that’s going on—so what would you want to convey to them from your experience?

Hank: I do think what they’re doing, it’s important. And I do know from experience these kinds of struggles raise a LOT of questions for people about the nature of all of this and what it’s actually going to take to end this. And they’re going to be presented with a lot of different outlooks and ideologies about “problem and solution.” And I do think that in terms of what BA and this Party [the RCP] represents and the need to check this out more, one of the things about my own experience is that, as I was fighting against this society, I did follow my convictions to wherever the fuck they led me. There was nothing in my life that said I was going to end up being a revolutionary communist. But there were things out there that I wanted to understand, that I wanted to know. And we didn’t have a party out there, but we did have advanced views and elements, and these things actually led me to where I am. And now there IS a Party, and this is the thing about BA and how he is challenging people to follow through on their convictions to really end these outrages.

Look, it’s confusing as a muthafucker out there for these people right now, what they’re trying to grapple with. But there IS a Party [the RCP] and a leader [BA] that’s actually done a lot of the work, that actually does have a scientific understanding of where all this shit that you’re going through actually comes from; they have a scientific understanding of what it’s actually gonna take to get rid of it. There is the leadership that’s been developed in the course of these years that actually is capable of leading revolution, based on the new synthesis of communism brought forward by BA. It’s something that they themselves need to actually get into, they need to check this out, AND compare and contrast to other things they’re going to encounter. I really do think that’s an important part of their development, in how they step forward. And for us, it’s important to recognize that these questions ARE out there in society, and that we need to make this accessible to people. They shouldn’t be “out in the desert wandering aimlessly.” It’s important for us to be in the mix and giving people this understanding of a way out. Because, again: I gravitated towards this; many other people went other ways—there is these other elements out there trying to shape and influence things. In all BA’s speeches, he always ends with a challenge to people to get with and check out this Party, and to always follow where your conviction leads you. They’re running up against some shit out there. The genie was let out of the bottle, and even for the conservative element, even for people on the “left,” it is hard to contain this fury that was released.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.