Case #27: October 2, 1968: The U.S. Hand in the Mexican Government’s Massacre of Hundreds of Students at Tlatelolco

| Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Bob Avakian has written that one of three things that has "to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better: People have to fully confront the actual history of this country and its role in the world up to today, and the terrible consequences of this." (See "3 Things that have to happen in order for there to be real and lasting change for the better.")

In that light, and in that spirit, "American Crime" is a regular feature of revcom.us. Each installment will focus on one of the 100 worst crimes committed by the U.S. rulers—out of countless bloody crimes they have carried out against people around the world, from the founding of the U.S. to the present day.

THE CRIME

On October 2, 1968—ten days before the start of the 19th Olympic Games in Mexico City—10,000 students and other supporters of a months-long student upsurge gathered for a meeting and rally in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco section of Mexico City. The students had made clear they weren’t going to march on the Olympic Village, but some 5,000 soldiers, 300 government tanks, jeeps, and armored cars, and hundreds of police surrounded the plaza nonetheless.

At 6:10 pm, flares were fired into the sky from a helicopter. Suddenly, out of nowhere, shots were fired from the upper floors of the Chihuahua apartment building overlooking the crowd, where many students were gathered.

The troops immediately responded by raking the crowd with machine-gunfire. Soldiers with fixed bayonets advanced from two sides—there was no escape. Tanks opened fire on the apartment complex, where student leaders had been speaking from a balcony. Inside the apartment building, a group of heavily armed men—each wearing a white glove on his left hand—detained the student leaders. The students were beaten, stripped to their underwear, and arrested.1

The Mexican government initially reported that four people had been killed and 20 wounded. The British newspaper Manchester Guardian reported that after careful investigation, it found that 325 probably died and the number could be much higher. Eyewitnesses described seeing “bodies of hundreds of young people being trucked away.” There were reports that bodies were burned or tossed into the sea. Thousands of students were beaten and jailed, and many disappeared.2

Ten days later, while 1,500 students in a military camp were being beaten and tortured, the Olympic ceremonies opened. Family members of the disappeared searched the prisons and morgues for missing loved ones, as tanks rumbled past billboards in a dozen languages proclaiming “Everything is possible with peace.”

The night of October 2 became known as the Massacre in Tlatelolco.

Bloody U.S. Fingerprints Covering the Massacre

The U.S. and Mexican governments immediately blamed student protesters for shooting first and triggering the Mexican police and military response. These were lies.

It wasn’t until three decades later—after some of the secret U.S. government documents about the events of October 2, 1968 were declassified and released—that the truth began to come out.3 It was discovered that an elite battalion of Mexican undercover police and military snipers, known as the Olympia Battalion—organized under the guidance of CIA “asset” and Mexico’s secretary of the interior Luis Echeverría—had infiltrated the crowd dressed as students and took up positions on the upper floors of surrounding buildings. Each one wore a white glove on his left hand so the soldiers would not mistake them for students. A machine gun was set up in the apartment where Echeverría’s sister-in-law lived. Among them were 10 marksmen. They were the ones who opened fire—on their own troops—provoking them to fire on the students and unleash the massacre.4 These documents and other reports also reveal that the fingerprints of the U.S.—the CIA in particular—are all over this bloody massacre.

CIA’s Secret U.S.-Mexico Spy Network Prepares for the Olympics

Mexico City housed the largest CIA headquarters in the hemisphere, from which they carried out operations throughout Central and South America. And it was the only country where the FBI operated openly. Winston Scott, the CIA station chief in Mexico from 1956 to 1969, had recruited at least 12 agents from among the top echelons of the Mexican government as paid informants: including Mexico’s then president, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, and Luis Echeverría, his successor as president, who while secretary of the interior was in charge of national security and the country’s police and security forces.5

In 1960, Scott had set up a secret spy network, code-named “LITEMPO,” operating out of the U.S. embassy in Mexico City, which provided the U.S. and Mexican governments with “sensitive political information neither wanted to receive through public channels.” LITEMPO would become the CIA’s “eyes on Tlatelolco.”6 During the months leading up to the October Olympics, the CIA and other U.S. agencies and top Mexican officials had secretly been in direct, daily contact to make sure the Olympic Games went off without a hitch and to monitor, assess, and take action against the growing student protests.

The chief of Mexico’s elite intelligence agency, the DFS (Dirección Federal de Seguridad), Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, also on the CIA payroll, passed daily reports from his own DFS agents to the CIA. And Scott delivered “‘a daily intelligence summary’ to President Díaz Ordaz, with a section on activities of Mexican revolutionary organizations and communist diplomatic missions.” Scott, in turn, relayed the views of Díaz Ordaz and other top officials to the U.S. ambassador and to CIA headquarters.7

Expediting Military Equipment to Mexico in Advance of Olympics

The U.S. and Mexico were not simply sharing intelligence. They were also preparing militarily to make sure the Olympics were not disrupted. In late spring and again in mid-summer 1968, the State Department requested that the Pentagon expedite Mexican orders of military equipment, for this reason: “In view of the importance which the Mexican Government gives to the smooth functioning of the Olympic Games, and our own Government’s desire to see that this event be as successful as possible.”8

Student Protests Erupt Nationwide...

In late July, the government’s violent repression of students protesting police brutality in Mexico City led to a student strike that quickly grew and spread rapidly to universities throughout the country. Through August and September this student movement attracted broad support—holding marches of hundreds of thousands—and became more determined in the face of police and military violence that left many students killed. In the eyes of the U.S. imperialists, Mexico had joined the list of world trouble spots, with buses burning on downtown corners of the city about to have the eyes of the world on it.

...and the U.S. and Mexico Prepare for a Clampdown

In response to the student upsurge, Echeverría had been put in charge of the “Strategy Committee”—a key working group of senior government officials created to fashion a response to the student protests. In Washington, the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) described “the committee as being at the heart of the government’s efforts to head off the students—whether by force or coercion.”9 The Olympia Battalion was one of the committee’s creations.

By September, Scott and other agents were meeting daily with Mexican leaders to assess developments and possible government responses to the growing student movement as the Olympics neared. The CIA and U.S. embassy were filing daily reports to the State Department and CIA headquarters in Washington.

The declassified U.S. government documents point to strong U.S. support for a forceful crackdown against the student uprising. A CIA dispatch applauded Díaz Ordaz’s September 1 presidential address promising to clamp down on student unrest. The U.S. embassy noted that the “permissive period” allowed by the regime had come to an end, and summed up their own view of the stakes for the Mexican government if they didn’t take decisive action: “Mexicans expect president above all to be strong decisive personality and, if permissive period extended too long, general public might conclude president lacks means or courage to deal with students. Ensuing loss of respect for president would, within Mexican political system, create grave dangers.”10

In late September, Dean Rusk, President Lyndon Johnson’s secretary of state, secretly reported that the “GOM (Government of Mexico) [is] virtually committed to forceful showdown with student militants,” but expressed concern over its “capability to prevent extremist disruption [of] Olympic Village, sports events, other Olympic facilities.” Meanwhile, Echeverría and Gutiérrez Barrios secretly assured the CIA that “no danger exists that the Olympic Games will be affected ... the situation will be under complete control very shortly, meaning a cessation of all acts of violence.”11

Then, just two days before October 2, the two most powerful men in U.S. Intelligence—current and former CIA directors Richard Helms and Allen Dulles—flew into Mexico City to meet with CIA station chief Winston Scott. What Helms, Dulles, and Scott discussed on the eve of the massacre has never been declassified. But this massacre has “Made in the USA” written all over it. The key lines of command of this slaughter—from the chief of staff of the Mexican military Luis Gutiérrez Oropeza, who posted the 10 marksmen; to the head of national intelligence, Gutiérrez Barrios; to Echeverría, secretary of the interior in charge of the strategic planning; to Díaz Ordaz—was connected to the CIA.

U.S. support for the Mexican government and its savage actions was also clear in the massacre’s aftermath. Neither the U.S. State Department nor President Johnson issued statements of condemnation of the Mexican government for this slaughter. Instead, the U.S. and Mexican governments continued to blame the students.12

THE CRIMINALS

Mexican President Díaz Ordaz oversaw and then lied to cover up the direct hand of the Mexican military in the massacre in Tlatelolco. Díaz Ordaz had been a paid CIA informant for years who was in regular contact with the CIA and the U.S. State Department. He provided the U.S. with crucial intelligence information every step of the way, and requested that the U.S. provide Mexico with military hardware and ammunition in the months leading up to October 2.

Luis Echeverría, as Mexico’s secretary of the interior, was in charge of the strategic planning for October 2, and directly oversaw the Olympia Battalion and the massacre. He, too, was a CIA asset. Echeverría was Mexico’s president from 1970 to 1976, at the height of Mexico’s dirty war against leftists, when over 500 were disappeared. In 2006, he was ordered arrested but was never tried on genocide charges for his role in the massacre at Tlatelolco.

Lyndon Johnson, the Democratic U.S. president in 1968, was overall responsible for the intelligence operations and other measures carried out by the CIA and other branches of the U.S. government. He was receiving secret messages and reports on the developments in Mexico more and more frequently in the period leading up to October 2.

Winston Scott was the CIA station chief in Mexico and was at the center of U.S. intelligence and covert operations before and after the massacre. Through his years-long cultivation of U.S. “assets” at the highest levels of the Mexican government, he was in position to provide constant reports to the CIA and Defense and State Departments about what was taking place on the ground, including how the Mexican government was planning to prevent the student uprising from disrupting or preventing the Olympic Games, and to convey U.S. advice, recommendations, and desires.

Richard Helms, Director of Central Intelligence, was responsible for the CIA’s role in Mexico overall and ensuring that a “successful” Olympic Games was able to take place in Mexico City.

THE ALIBI

The Mexican government claimed that the students were responsible for the massacre, and that the initial shots had come from among students on the upper floor of the Chihuahua building overlooking the plaza. Díaz Ordaz said the massacre had been “carefully planned” by pro-Soviet and pro-Cuban radical students who had been at the center of the initial attack, as part of Cuban and Soviet efforts to disrupt the Olympic Games and destabilize the Mexican government. The U.S. publicly supported and echoed Mexico’s claims.

THE ACTUAL MOTIVE

Mexico City was the first Third World country to host the Olympic Games. Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) saw the Olympics as an opportunity to showcase to the world the country’s economic development and stability. For the U.S., it was a chance to show off the benefits of U.S. imperialist-led economic and political development, which by 1968 was being challenged by revolutionary China’s socialist road, the Soviet-Cuban model of development, and the national liberation struggles taking place around the world.

Mexico’s student movement erupted and spread across the country against this backdrop. The Díaz Ordaz regime and its U.S. overseers viewed the gathering force of the student movement with great alarm, fearing the student protests could grow to overshadow, or force the cancellation of, the games on which they had so much riding, and possibly threaten the stability of the Mexican government. The U.S. rulers were determined not to allow this.

For all these reasons, the U.S. and Mexican governments were hell-bent on not only containing the student uprising, but brutally drowning it in blood when that became necessary, and to continue to violently repress and disappear students and leftists under Mexico’s president—and CIA asset—Echeverría during the “dirty war” of the early 1970s.

1. “Before the World Arrived,” Jonah Walters, The Jacobin, May 23, 2018. [back]

2. “October 2 is not forgotten, Upsurge and Massacre in Mexico 1968—Part 2: Blood at Tlatelolco,” revcom.us, October 4, 1998. [back]

3. The National Security Archive began investigating the Tlatelolco massacre in 1994, through records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act and archival research in both Mexico and the United States. In 1998, the archive posted its first 30 declassified U.S. documents on 1968. All of them come from the secret archives of the CIA, FBI, Defense Department, the embassy in Mexico City, and the White House. [back]

4. “Tlatelolco Massacre: U.S. documents on Mexico and the Events of 1968,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 99, edited by Kate Doyle, published October 10, 2003; “Mexico’s 1968 Massacre: What Really Happened?” Broadcast on NPR’s All Things Considered, December 1, 2008. [back]

5. “LITEMPO: The CIA’s Eyes on Tlatelolco—CIA Spy Operations in Mexico,” Jefferson Morley, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 204, October 18, 2006 (originally published in Proceso magazine, October 1, 2006). [back]

6. Ibid. Each agent was identified in CIA files by a specific number: LITEMPO-2 was President Díaz Ordaz, and his nephew was LITEMPO-1; Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, head of DFS, was LITEMPO-4; and Luis Echeverría was LITEMPO-8. [back]

8. K. Doyle, op. cit. Document 84, State Department Letter—May 24, 1968. [back]

9. Ibid., Introduction. [back]

10. Ibid., Document 13, September 6, 1968. [back]

11. Ibid., Document 34, September 25, 1968. [back]

12. The following morning, the International Olympic Committee met in secret, and IOC President Avery Brundage announced afterwards that the Games would proceed as scheduled and that local student problems had no connection with the Olympics. [back]

In July 1968, the Mexican government’s violent repression of students protesting police brutality led to a student strike that rapidly spread to universities. Here a great throng of demonstrators gathers in the Zócalo, or Constitution Square, in the heart of Mexico City, August 14, 1968, at the conclusion of a five-mile march through the city. (Photo: AP)

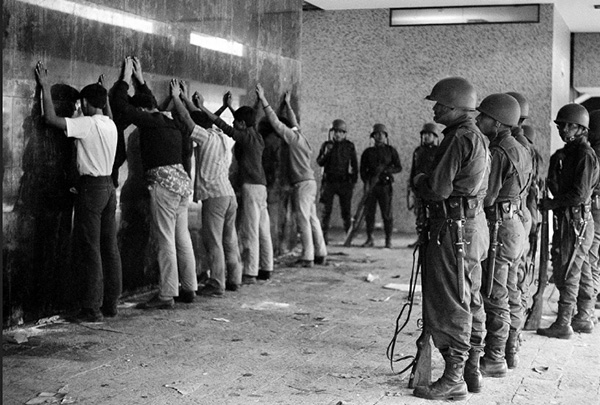

Mexican troops guard young men arrested after a night of protests on October 2, 1968. (Photo: AP)

Mexican army soldiers beat demonstrators in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas area of Mexico City, a slaughter that came to be known “Tlatelolco massacre.” (Photo: AP)

Q&A: Would Mexico And Central America Still Be the US Backyard After the Revolution?

Excerpt from “Why We Need An Actual Revolution And How We Can Really Make Revolution”

A speech by Bob Avakian

Watch the whole speech, spread it, fund it

Find out more about this speech—and get organized to spread it

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: