El Salvador: Tormented for a Century by U.S. Capitalism‑Imperialism

| revcom.us

2019—migrants travel north from Central America. Over the past century, U.S. imperialism has plundered and devastated the smallest of the Central American countries, El Salvador, and turned it into a hellish deathscape of violence and poverty for the masses of people there, causing tens of thousands to make the dangerous journey north. Photo: AP

Anyone trying to understand why tens of thousands of immigrants from Central America and Mexico—including children—make dangerous journeys across hundreds of miles trying to enter the U.S. needs to confront this fundamental truth Bob Avakian expresses:

Now I can just hear these reactionary fools saying, “Well, Bob, answer me this. If this country is so terrible, why do people come here from all over the world? Why are so many people trying to get in, not get out?” …Why? I’ll tell you why. Because you have fucked up the rest of the world even worse than what you have done in this country. You have made it impossible for many people to live in their own countries as part of gaining your riches and power. (BAsics 1:14)

The following article outlines some of the ways over the past century that U.S. imperialism has plundered and devastated the smallest of the Central American countries, El Salvador, and turned it into a hellish deathscape for the masses of people there.

1904–1944: The “Coffee Republic,” the “American Cure,” la Matanza (the Massacre)

In 1904 U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt declared to the world that the U.S. had a “right” to exercise “international police power” in Latin America and the Caribbean--a warning to other powers to keep out of what the U.S. considered its “backyard.” El Salvador became a “Coffee Republic”—with a handful of wealthy plantation owners while the masses of people lived under harsh oppression and in extreme poverty.

Protest and unrest grew in El Salvador during the 1920s and 1930s. In 1932, the government responded to a peasant strike by massacring about 30,000 people, or 4% of the population, in one week—this was called la Matanza. Ferocious repression followed for the next 12 years under the regime of Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, a U.S. puppet and open fascist sympathizer.

In 1904, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt declared to the world that the U.S. had a “right” to exercise “international police power” in Latin America.1 This brazen declaration was a warning to rival powers to keep their military presence out of what the U.S. considered its “backyard” and a “justification” for the U.S. military to “extend its ‘sphere of influence’ in the Caribbean, Central America, and smaller countries of South America....” It immediately led U.S. financiers to “believe that increased intervention and policing by the U.S. in Central America would provide greater peace and financial stability in the region.”2

El Salvador soon became one of the world’s largest producers of coffee—known as the “Coffee Republic.” A handful of wealthy plantation owners secured financing that enabled them to enrich themselves while millions of Salvadorans lived in poverty. This process was called the “American Cure ... a three-part formula of debt, discipline, and exports.” Thousands of peasants were displaced from their farms and forced to work on coffee plantations, where they were paid with a small amount of scrip that could only be used at company stores and two bean tacos daily.3

Protest and unrest grew in El Salvador throughout the 1920s as coffee prices fell internationally and large plantation owners, backed by the government, slashed wages, and confiscated even more land from the peasants. In 1932, an uprising, primarily of indigenous peasants in El Salvador’s western coffee regions, began after the government prevented Communist Party members elected to the national legislature from taking their seats.

The government responded to a peasant strike by “massacring an estimated 30,000 people, or 4% of the population, in one week”4—what was called la Matanza. The U.S. and Canada sent warships to aid the Salvadoran government.5 The warships weren’t used because the Salvadoran military was able to crush the uprising by themselves. Ferocious repression throughout the country followed the massacre—and continued for the next 12 years under the regime of Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, a U.S. puppet and open fascist sympathizer.6

1944–1979: U.S.-Backed Coups, Massacres, Repression

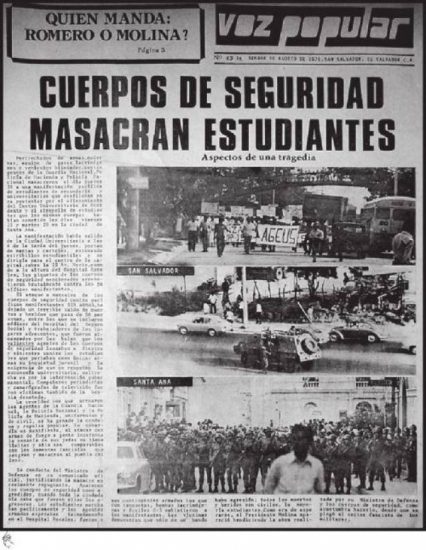

Headline reads: “Security Forces Massacre Students.” It describes the shooting of student protestors from the University of El Salvador on July 30, 1975. Source: Zinn Education Project.

The 1950s through the 1970s were marked by a series of regimes in El Salvador dominated by the U.S.-backed military and wealthy plantation owners. In October 1979, a U.S.-backed coup brought another junta to power. It was immediately recognized by the U.S. government under President Jimmy Carter. Deadly repression was unleashed against protesters in San Salvador and other cities. Massive U.S. funding and support for the regime began pouring into the country. Photo: AP

A series of protests and strikes in the spring of 1944 forced the government from power and Hernández Martínez into exile. A few months later, Osmín Aguirre y Salinas, an army colonel and former chief of police, led a military-backed coup that unleashed bloody repression of students, labor organizations, and civilian political parties.7 Aguirre y Salinas’s regime was “legitimized by immediate recognition from the United States.”8

Internationally, the decades beginning in the 1950s were increasingly shaped by “Cold War” contention between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.9 Virulent, violent anti-communism became the cornerstone of U.S. global policy. In El Salvador, these decades were marked by a series of governments dominated by the military, and an economy dominated by wealthy plantation owners, both of them linked to the U.S.10 In 1954, the U.S., under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, orchestrated support for a coup it was preparing against the leftist president of Guatemala. The Salvadoran government faithfully assisted the U.S. by putting an anti-communist resolution before the Organization of Central American States, isolating Guatemala and forcing it to withdraw from the organization, thus paving the way for a U.S.-backed coup.11

In 1960, the U.S. withheld recognition from a Salvadoran junta (ruling group composed of military and civilian leaders) that had promised elections. Months later, a right-wing countercoup toppled the junta before the scheduled elections and seized power. The countercoup was facilitated by the U.S., which soon announced its support for the illegitimate government.12

Protests mounted throughout the 1970s, and the government responded with ferocious repression. Among the government massacres: In 1975, police fired on students protesting a Miss Universe contest—dozens were killed and “disappeared.” In 1977, more than 200 protesters were killed and hundreds more wounded by government troops when tens of thousands of people gathered peacefully in the central plaza of San Salvador to protest election fraud.13 Right-wing death squads—which had been built up, trained, organized, and even provided target lists by the U.S. military and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents—began to target and “disappear” hundreds of left-wing opponents.14

In October 1979, a U.S.-backed coup brought another junta to power. It was immediately recognized by the U.S. government under President Jimmy Carter. Deadly repression was unleashed against protesters in San Salvador and other cities. Massive U.S. funding and support for the regime began pouring into the country.15

1980-1992: Civil War, Death Squads and Genocide, Depopulation

After Archibishop Romero, who had called on an end to the U.S. aid to the Salvadoran military, was gunned down in 1981, civil war broke out. Genocidal repression against poor farmers in El Salvador’s rural areas was a major focus of the U.S.-directed war against guerrilla forces backed by the Soviet Union, which was at the time a powerful imperialist rival of the U.S. worldwide. On December 11, 1981, a U.S. trained and armed battalion entered the northern village of El Mozote, ostensibly to search for guerrillas. They found none. Nevertheless, they executed more than 800 civilians, including children.

1981—Death squad victims in San Salvador, El Salvador. In a 12-year war beginning in 1980, right-wing governments backed by the U.S. killed and tortured more than 70,000 people, in a country with a population of about six million.

From 1980 to the early 1990s, the U.S. provided an estimated $6 billion in military aid to the Salvadoran regime. The Salvadoran military grew from an estimated 7,000 in 1979 to about 53,000 by 1986. There were at least 11,000 additional civilian counter-revolutionary forces, many of them active in death squads. Here, government soldiers with a howitzer gun in Osicala, El Salvador, 1987. Photo: AP

In March 1980, Archbishop Oscar Romero, who had called on Carter to end U.S. aid to El Salvador’s military, was gunned down as he was saying Mass at a hospital chapel. Targeted killings of oppositional leaders and slaughter of protesters intensified. The government began genocidal campaigns in rural areas, calling it “agrarian reform.” Several guerrilla groups, backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba, joined to form the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), which became the main force fighting the U.S.-backed government. Civil war erupted.

From 1980 to the early 1990s, the U.S. provided an estimated $6 billion in military aid to the Salvadoran regime. The Salvadoran military grew from an estimated 7,000 in 1979 to about 53,000 by 1986. There were at least 11,000 additional civilian counter-revolutionary forces, many of them active in death squads such as the Maximiliano Hernández Martínez Anti-Communist Brigade.16 The U.S. also routed significant funds and training to the Salvadoran military through allies such as Argentina, Chile, and Israel17 and funneled $2.2 million to fascist political parties to help tighten their grip on power.18

Genocidal repression against poor farmers in El Salvador’s rural areas was a major focus of the U.S.-directed war. In December 1981, the Atlacatl Battalion, an elite unit of the Salvadoran military, carried out a horrific massacre in the village of El Mozote. “The residents were rounded up overnight and the next day, December 11, were killed. The Atlacatl Battalion maimed, shot, raped, and dismembered hundreds of unarmed men, women, and children. Nearly half of the victims are believed to have been under 10 years old. Estimates of the total murdered on that day range from 200 to over 1,000.”19 The battalion “decapitated men in a church and bayoneted a child to death and slaughtered entire families.”20

The Atlacatl Battalion was specially trained by the U.S. military at the School of the Americas at Fort Benning, Georgia. It was considered the “pride of the United States military team in San Salvador.”21

Rural farming areas of El Salvador, a small country about the size of the state of Massachusetts, were “pummeled by the most intensive and prolonged aerial bombardment in the history of the Western hemisphere. The air force dropped phosphorous bombs and napalm on forested hillsides and farmlands, poisoning the earth for many seasons. The army swept through the countryside, torching whole farming communities and slaughtering livestock.”22,23

By the time a treaty ending the war was signed in 1992, about a million Salvadorans had been driven from their homes24—“a third of the population either fled the country as refugees or [was] displaced internally.”25 Much of the country lay in ruins. And over 75,000 civilians had died at the hands of government forces supported, trained, and funded by the U.S.26

1992–the Present: A Cascade of Environmental, Social, and Economic Catastrophes

Decades of intense coffee production and massive government onslaughts during the civil war have depleted once fertile agricultural land and poisoned much of El Salvador’s remaining water and soil. Today, El Salvador is experiencing a “multilayered crisis of water scarcity, contamination, and unequal access that affects a quarter of the country’s population,” and “more than 90 percent of surface water sources in the country are contaminated.”

Decades of intense coffee production and massive government onslaughts during the civil war have depleted once fertile agricultural land and poisoned much of El Salvador’s remaining water and soil. Since the 1960s, about 85 percent of the country’s forests have disappeared, and over 50 percent of El Salvador is no longer suitable for food cultivation. The entire country is “perilously close to facing large-scale desert formation.”27 El Salvador is experiencing a “multilayered crisis of water scarcity, contamination, and unequal access that affects a quarter of the country’s population of 6.4 million,” and “more than 90 percent of surface water sources in the country are contaminated.” At least 600,000 people in rural areas have no access to water, and hundreds of thousands more have limited or intermittent access.28

Environmental devastation has made El Salvador more vulnerable to extensive damage from severe natural events such as volcanos, earthquakes, hurricanes and landslides set off by torrential rain. October 2020, the upper part of San Salvador volcano was set in motion by torrential rains. Here, people search for bodies buried in the mud where homes once stood, in Nejapa, El Salvador. Photo: AP

As in Central America overall, environmental devastation has made the country more vulnerable to extensive damage from severe natural events such as volcanoes, earthquakes, hurricanes, and landslides set off by torrential rain. Two hurricanes that hit the country in late 2020 destroyed entire villages. The anti-poverty organization Oxfam estimates that as of late December 2020, 800,000 people were still homeless in El Salvador and other Central American countries because of these hurricanes.29

In 2006, El Salvador entered the U.S.-dominated Dominican Republic—Central America Free Trade Agreement” (CAFTA-DR). It required and has accelerated “restructuring” the economies of the countries who joined it.30 And this has opened the floodgates to a massive influx of American agricultural and industrial goods that have weakened domestic economic activity, especially farming. A report by the Council on Hemispheric Affairs concluded that in El Salvador and other countries, CAFTA-DR has contributed to the elimination of many small farms and greater “food insecurity”31 (translation: hunger and starvation), driving more people into El Salvador’s cities. And many of these people try to migrate to the U.S. to find a means of survival. Environmental deregulation CAFTA-DR mandated also has enabled mining companies based in the U.S. and other imperialist countries to “strike gold”32—and their mining has further poisoned mountain zones.

During the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans who fled U.S. sponsored terror during the civil war settled in barrios of Los Angeles, where groups of youth formed gangs, including for self-protection. In the 1990s, many of these youth were deported to El Salvador. Here, Salvadorans arrive at the El Salvador international airport after being deported from the U.S., February 1999. Photo: AP.

Horrific violence plagues the masses of people of El Salvador, carried out by gangs and police/military forces, sometimes acting together. The country has one of the highest homicide rates in the world,33 and this violence is a major factor driving people out of the country. But seldom mentioned is that the roots of El Salvador’s violent gangs are in the U.S. During the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans who fled U.S.-sponsored terror during the civil war settled in barrios of Los Angeles, where groups of youths formed gangs, including for self-protection. In the 1990s, many of these youths were deported to El Salvador. A law signed by President Bill Clinton in 1996 made it far easier for the government to quickly deport people, including lawful permanent residents, who had been convicted of certain minor crimes.34 Some of the deported youths took their gang allegiances and culture with them, as they returned to the crushing poverty and police/military violence of El Salvador’s cities.

So ask yourself—what could compel people to risk everything, even the lives of their children, to cross a continent and try to enter the U.S.?

Footnotes:

1. Theodore Roosevelt’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, OurDocuments.gov [back]

2. “Empire, Public Goods, and the Roosevelt Corollary,” Kris James Mitchener, The Journal of Economic History [back]

3. Information and quote from the book Coffeeland: One Man’s Dark Empire and the Making of Our Favorite Drug, by Augustine Sedgewick [back]

4. January 22, 1932: La Matanza (“The Massacre”) Begins in El Salvador, Zinn History Project [back]

5. “Unintended Consequences: U.S. Military Interference in El Salvador,” Blake Bergstrom, James Madison University [back]

6. Hernández Martínez, Maximiliano, Our Campaigns [back]

7. Latin American Election Statistics, El Salvador; University of California, San Diego, Collections [back]

8. A Century of U.S. Domination Created the Immigration Crisis, Mark Tseng-Putterman, https://medium.com/s/story/timeline-us-intervention-central-america-a9bea9ebc148 [back]

9. From 1917 until the mid-1950s, the Soviet Union (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, or USSR) was the world’s first socialist state. This marked a huge advance for humanity. However, following the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953, capitalism was restored in the Soviet Union. By the late 1970s, the Soviet Union had become a capitalist-imperialist power (while continuing to falsely claim to be “communist”), and it was locked in a fierce, reactionary rivalry with the U.S. for global dominance. Wars between U.S. and Soviet-backed forces erupted in several parts of the world, and in El Salvador an insurgency of masses of people was greatly influenced by pro-Soviet political and military forces. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. [back]

10. Bergstrom, page 21 [back]

11. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, pgs. 421-426 [back]

12. U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian [back]

13. El Salvador: Uprising, NACLA Report, September 25, 2007 [back]

14. History of El Salvador, Teaching Central America [back]

15. Mass Atrocity Endings, El Salvador, Tufts University Case Studies [back]

16. “Rightist Death Squad Kills Four in El Salvador,” New York Times, October 8, 1983 [back]

17. American Crime Case #38: 1980-1992 – The U.S. Back’s El Salvador’s Death Squad Government, Revolution, July 9, 2018 [back]

18. “CIA Said to Aid Salvador Parties,” New York Times, May 12, 1984 [back]

19. December 11, 1981: El Mozote Massacre in El Salvador, Zinn History Project [back]

20. Ibid. [back]

21. “How U.S. Actions Helped Hide Salvador Human Rights Abuses,” New York Times, March 21, 1983 [back]

22. Ibid. [back]

23. In December 1983, at a time when death squads were killing hundreds of people a week and as opposition to the murderous war intensified in the U.S. and other countries, U.S. Vice President George Bush traveled to El Salvador to advance U.S. efforts to back the war against the anti-government forces. Bush met with top government officials and other major figures, including Roberto d’Aubuisson, a former U.S.-trained intelligence officer and head of the fascist Arena party. Bush made some public statements about opposing the Salvadoran death squads—but in reality, death squads, and the overall genocidal war backed by the U.S. continued for another nine blood-drenched years. [back]

24. The Pacification of Central America, James Dunkerley, Institute of Latin American Studies [back]

25. Destruction of a Way of Life, El Salvador Watch, November 1997 [back]

26. El Salvador, Center for Justice and Accountability [back]

27. Destruction of a Way of Life, El Salvador Watch, November 1997 [back]

28. “Once Lush, El Salvador is Now Dangerously Close to Running Dry,” National Geographic, November 2, 2018 [back]

29. TPS Can Promote Stability and Recovery for Central American Countries Hit by Recent Hurricanes, Center for American Progress, December 2020 [back]

30. The Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), Every CSRReport.com [back]

31. CAFTA-DR Governments in Contrast to Small-Scale Owners Parcel Engine of Development, Council on Hemispheric Affairs [back]

32. What “Free Trade” Has Done to Central America, Foreign Policy in Focus [back]

33. “The Real Migration Crisis is in Central America,” Foreign Affairs, April 13, 2021 [back]

34. “Deporting People Made Central America’s Gangs. More Deportation Won’t Help,” Washington Post, July 20, 2017 [back]

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: